Posts tagged St. Joseph’s Day

Mardi Gras Music Series- BO DOLLIS & THE WILD MAGNOLIAS

3Bo Dollis, Sr. has 1 of the greatest, most expressive voices in all the Mardi Gras Indian Kingdom. He has recorded 1 of the top Mardi Gras albums of all time, and has recorded some of the most famous Mardi Gras tunes in Carnival history. I met Bo Dollis,Sr. with my client and good friend, June Victory. Bo was sitting on his little scooter, which helps him get around. Bo’s wife runs a salon in Mid City where they give haircuts, etc. Bo hangs around there.

Listen to Handa Wanda Parts 1 & 2 by the Wild Magnolias

Handa Wanda, Pt. 1

Some of the below bio is from wildmagnolias.net

Theodore Emile “Bo” Dollis was born in New Orleans in 1944. His father was from Baton Rouge, and his mother came from a French-speaking Creole family in St. Martinville, Louisiana. Bo grew up in the central city, an old, run-down commercial-residential uptown neighborhood behind the grand St. Charles Avenue mansions. He was first attracted to the African-Caribbean-American tradition of Carnival Indians while still a youngster.

Bo’s career as a performer and his development as one of the classic singers in the history of the New Orleans recording began when, as a junior in high school, he secretly started attending Sunday night Indian “practice” in a friend’s back yard. He followed The White Eagles tribe, playing and singing the traditional repertoire. In 1957 he masked for the first time with The Golden Arrows, not telling his family of his involvement with the Indians. He made his suit at someone else’s house and told his folks he was going to a parade. Hours later his father discovered him, having recognized his son in the street, underneath a crown of feathers.

Bo Dollis’ name is virtually synonymous with the Wild Magnolias Mardi Gras Indian Tribe. He is clearly the most popular Indian Chief (chosen in 1964) in New Orleans, with everybody wanting to see him in his hand-crafted suit on Mardi Gras or St. Joseph’s Day. Bo has been a legend almost from the beginning, because he could improvise well and sing with a voice as sweet as Sam Cookie, but rough and streetwise, with an edge that comes from barroom jam sessions and leading hundreds of second-lining dancers through the streets at Carnival time.

In 1974 they released the legendary Wild Magnolias album, backed by a New Orleans all-star band that included Willie Tee, his brother Earl Turbinton, Jr. on saxophone, Snooks Eaglin on guitar and Alfred “Uganda” Roberts on percussion. This band’s performance at the Bottom Line in New York made the Magnolias headline news.

In 1975, Dollis and Monk Boudreaux, Chief of the Golden Eagles, recorded James “Sugarboy” Crawford’s 1954 R&B hit Jackomo, Jackomo. There is contrast in their vocal phrasing, and each swings the story line at a slightly different pace; nonetheless, the unity of spirit shines through. You can hear the closeness of these two childhood friends, the only two professional Chiefs performing in New Orleans. In 1970, they appeared at the first New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. Shortly afterward, they collaborated on the classic Mardi Gras song Handa Wanda. Seldom do they sing together in practice.

The Wild Magnolias and The Golden Eagles have taken Bo Dollis and Monk Boudreaux from the ghettos and brought them to places like Carnegie Hall in New York City, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, DC, London, Nice and Berlin. Where ever they go, listeners will hear an authentic music to which New Orleans owes so much.

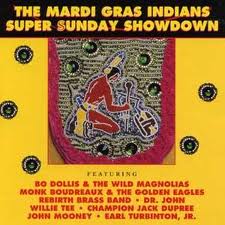

In the 1980’s, June Victory joined the Wild Magnolias as lead guitarist. On the Mardi Gras Indians Super Sunday Showdown CD (Rounder, 1992), June has 2 arrangements, Oops Upside Your Head & Battlefront. After June Victory left the Magnolias, June Yamagishi took his place.

In January 2009, Bo Dollis received the Best of the Beat Lifetime Achievement Award from OffBeat Magazine. OffBeat contributor John Swenson interviewed Bo about his life and art:

Were your parents music fans?

No.

So did you listen to the radio growing up? Jazz, R&B?

No.

Gospel?

Yeah. I did sing in church. Everybody went to church, my mama and brothers went. It was just singing. I didn’t think anything of it. I would sing with the choir at church. We sang around the house. People would come to hear me sing.

I can’t say it like I wish I could anymore. I sang… what’s his name? Fats Domino! I wanted to be like him. People would say, “He sounds just like Fats Domino.”

You got introduced to the Indians by a neighbor, right?

The Indians were what I was interested in. He was an Indian chief and he was right there where I lived and I used to watch him make an Indian suit. He was with the White Eagles and I used to watch him. He’d give me little pieces and I tried to make one myself. So I made my first Indian suit. I ended up with the Wild Magnolias. I went with the White Eagles but they had a Big Chief and I could only be a Red Indian with them so I left. So I ended up with the Wild Magnolias because there I got a spot. I got with them and I got to be a Flag Boy. I’ve been with them ever since.

You must have been a hell of a Flag Boy because you moved up to Big Chief pretty quickly.

I had a good voice and they wanted me to sing. With the White Eagles I couldn’t sing. See the Indians can’t sing. They can answer, but they can’t sing. We walk down the street and I sing [amazingly, his voice opens up to full strength as he sings a patois that ends with “Down the street here I come”].

You put on a suit. You look good. I was… young. They say they want me to be chief, and some of the people in there were 35, 55. I said, “I don’t wanna be no Big Chief,” and everybody said, “You’re good! You gotta sing. You’re Big Chief.”

I wanted to be the Spy Boy. I was young and I could move around. I wanted to spy out on the other tribes.

Did you start writing songs for the Indians right away?

I would sing, and what you hear Indians sing today is what I was singing then. You don’t hear too many of the new Indians singing the older songs, but it’s more of the stuff that I used to do. They don’t know the words to the songs. They may know the title, but they don’t know the words to the song. They don’t know what they’re doing. They not Mardi Gras Indians they just talkin’… they just crazy.

When you started out, were the old timers then doing different songs or different lyrics to songs?

Maybe one or two guys, but they all sang the same songs.

It was a ritual.

Right. But they don’t have that now. They don’t know that.

So you think some of that ritual is lost.

Oh yeah. All that’s lost. They don’t try. There’s no more Indians

When you were coming up, you were part of a whole generation of young people who were becoming Indians, right?

Yeah. We were young. One time with the Indians you could go from up here to the Treme and back, marching. Now you can’t go from here to up the block because the suits are too big. [laughs] They got to be carried on a cart because the suits are too big for the people, too heavy. It’s pretty…

In the old days you traveled light because you had to cover a lot of distance.

Right. All except the chief, he always had the suit.

Gerard: Back then, the other Indians except the Chief, the Second Chief, the Trail Chief, the Spy Boy and all, they might wear four or five patches. Now they wear 20 patches.

Dollis: Everybody wants to be chief. [laughs]

Gerard: You know that Flag Boy might have a flag in his hand, the Wild Man might be carrying a wooden shotgun, that’s how you tell who they are. The Chief is supposed to have the biggest crown, that’s how you tell who he is. Today you might see some Flag Boy with a bigger crown than the Chief! When I started out, you had five, six patches. Now I’ve been doing it a while so I got 20 patches, but nobody starts with five or six patches now. Now I don’t think anybody want to be an Indian except for the Wild Man.

Was it a difficult decision to record the Mardi Gras Indian music, which was considered a secret ritual up to that time?

No, no, no. I was all for it. I always loved to sing. Quint came to an Indian practice. I didn’t know if I could stay in tune. I never wrote music but I could sing. Whatever the band played, I could sing it. Anywhere you go, I could go. I can’t write music, but I can feel whatever they do.

Gerard: Quint came to an Indian practice, he didn’t know who my dad was. My dad came in and started singing and Quint was like, “Whoa, who’s this voice? We’re going to put you in the studio.” So he just started singing.

This was 1970, which was also the first year of jazz festival.

Yeah. We led the first parade. Me and Monk. I put my suit on and started singing, leading a second line, down Canal Street all through the French Quarter, singing all the way to Congo Square and the people followed along all the way. I was singing. With all the other Indians.

That was the year you opened up Mardi Gras Indian culture to a whole new audience.

Gerard: A lot of people were scared of the Indians back in those days. They heard about all the violence, so they were more scared than anything else.

Dollis: We tell about the days way back they was wild, wild, wild; I mean they was cutting, killing and shooting. The uptown and the downtown would fight. We didn’t want that. So we stopped. Tootie Montana was big on that. He wanted to get it straight because he was beautiful. He looked so good. Then everybody wanted to be… beautiful. So we got all the Indians and all the chiefs to stop the violence.

Gerard: We all just wanted to change it. We fought with pretty suits instead of our hands and knives and guns. Back in the old days we’d fight in the day then at night we’d buy each other drinks in the bar. But when it comes to guns, there’s no buying drinks after the fight. Once the guns come out, you’re either going to jail or you’ll be six feet under.

Dollis: The gangs today, they kind of like looking like those old Indians were with the way they fight and shoot.

Maybe they can stop the violence again like you guys did.

They won’t until they can find somebody to lead them there. They need a chief to take care of it.

Were you close with Tootie Montana?

I was friends with Tootie, but I didn’t see him so much. I would see him at Jazz Fest or Mardi Gras day or Super Sunday. He knew me and I knew him. We both loved what we do.

When you would meet Tootie or another chief on the street during Mardi Gras, you had a ritual exchange. Did you really try to get the upper hand or was everybody cool about it?

The people wanted to see us confront each other and yell and sing or something like that, but we knew each other and what to do. A lot of times it was about your suit and showing that off. I used to try and see the other chief’s suit before he sees me. I used to try and see them before they come out of their house. One time, I went to a house to look and his crown was so big he couldn’t get out his front door! That’s how big some of them got.

After Katrina a lot of the neighborhoods are gone and not as many Mardi Gras Indians are around. Do you think it will ever come back to what it once was?

Since the storm… everybody now… tryin’… it’s only for money. Ain’t nobody….

But surely some of the Indians are keeping it alive.

Yeah, they’re keeping it alive, but nobody knows what they should be doing. What I wanted to do, I wanted somebody to talk to all the Indians, all over the city and write a book. So we could have all that information documented. I got nobody who could do it. ’Cause you can’t even find all the Indians I know about. I could talk to them myself, I know how to talk to them. I wanted the older people to tell about it. I wanted to get that done. But now I can’t… talk.