Mardi Gras Music

PROTEUS & ORPHEUS ROLL ON LUNDI GRAS!!

0Proteus had some of the most beautiful floats last year, my Float of the Year 2010 was this Proteus float:

KREWE OF PROTEUS

Proteus is the Second oldest Parade at New Orleans Mardi Gras. Founded in 1882, Proteus (“PROH tee us”) The shepherd of the Oceans, is an early sea-god, one of several deities whom Homer the Old Man of the Sea has always held elaborate masked Tableau Balls and the most beautiful Street Parade to date.

in 1893 the Krewe first introduced the tradition of call outs, Where masked costumed Krewe members invited ladies in attendance to step out on the dance floor with them. This custom was then adopted by many other Krewes including Rex.

The Identity of the King of Proteus is never revealed to the public. His Parade float is a giant Seashell and very march part of the New Orleans Carnival scene for generations.

Proteus did not parade from 1993 – 1999 but returned to parading on Lundi Gras (The Monday before Mardi Gras Day, Shrove Tuesday, or Fat Tuesday) in 2000. The Parade of The Krewe of Proteus Follows the Traditional Uptown or St. Charles Route ending on Canal Street. The actual Krewe of Proteus parade floats are still using the original chassis from the early 1880’s.

The Mythical Proteus

The son of Poseidon in the Olympian theology ( Homer,Odyssey iv. 432), or of Nereus and Doris, or of Oceanus and a Naiad, and was made the herdsman of Poseidon’s seals, the great bull seal at the center of the harem. He can foretell the future, but, in a mytheme familiar from several cultures, will change his shape to avoid having to; he will answer only to someone who is capable of capturing him. From this feature of Proteus comes the adjective protean, with the general meaning of “versatile”, “mutable”, “capable of assuming many forms”: “Protean” has positive connotations of flexibility, versatility and adaptability.

Proteus is also known as a shape shifter and can assume the guise of anyone or anything he so chooses. When held fast despite his struggles, he will assume his usual form of an old man and tell the future.

The so-called Old Man of the Sea, is a prophetic sea divinity, son of either Poseidon or Oceanus. He usually stays on the Island of Pharos, near Egypt, where he herds the seals of Poseidon. He will foretell the future to those who can seize him, but when caught he rapidly assumes all possible varying forms to avoid prophesying.

Proteus [PROH-tee-us], like all six of Neptune’s newly discovered small satellites, is one of the darkest objects in the solar system — “as dark as soot” is not too strong of a description. Discovered by Stephen Synnott, Like Saturn’s satellite, Phoebe, it reflects only 6 percent of the sunlight that strikes it. Proteus is about 400 kilometers (250 miles) in diameter, larger than Nereid. It wasn’t discovered from Earth because it is so close to Neptune that it is lost in the glare of reflected sunlight. Proteus circles Neptune at a distance of about 92,800 kilometers (57,700 miles) above the cloud tops, and completes one orbit in 26 hours, 54 minutes. Scientists say it is about as large as a satellite can be without being pulled into a spherical shape by its own gravity. Proteus is irregularly shaped and shows no sign of any geological modification. It circles the planet in the same direction as Neptune rotates, and remains close to Neptune’s equatorial plane

Orpheus is a Super Krewe founded by Harry Connick, Jr. They have Celebrity Monarchs-

Celebrity monarchs

- 2010: Steve Zahn, Sean Payton, Imagination Movers, Paul Mainieri

- 2009: Joan Rivers, James Belushi, Reno 911!

- 2008: Hélio Castroneves, Sidney Torres, Lance Bass, Kevin Meaney, Salt-n-Pepa, Christian LeBlanc, Ricky Paull Goldin, Sean Payton, Josh Gracin

- 2007: Patricia Clarkson, Sean Payton, Harry Connick, Jr.

- 2006: Steven Seagal, Josh Hartnett

- 2005: Sawyer Brown, Toby Keith

- 2004 Dominic Monaghan, Brad Paisley, Nicole Miller, Harry Connick, Jr. [9]

- 2003 Travis Tritt, Harry Connick, Jr.

- 2002

- 2001 Glenn Close (grand marshall), Whoopi Goldberg, Hoda Kotb, Harry Connick, Jr. [12]

- 2000 Whoopi Goldberg (grand marshall),

- 1999 Sandra Bullock, Forest Whitaker,

- 1998

- 1997 Stevie Wonder, Quincy Jones, Anne Rice, Harry Connick, Jr.

- 1996 The Road Rules gang from MTV, Laurence Fishburne, Jay Thomas (’96 King of Orpheus), Anne Rice (’96 muse of Orpheus), Harry Connick, Jr.

- 1995 Anne Rice

- 1994 Little Richard, Branford Marsalis, Vanessa R. Williams, Dan Aykroyd, Harry Connick, Jr.

Other celebrity monarchs for the Krewe of Orpheus include Camryn Manheim, Debbie Allen, Tommy Tune, James Brown, David Copperfield, Delta Burke, Gerald McRaney, Josh Gracin and Christian LeBlanc.

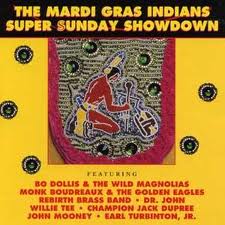

Mardi Gras Music Series- BO DOLLIS & THE WILD MAGNOLIAS

3Bo Dollis, Sr. has 1 of the greatest, most expressive voices in all the Mardi Gras Indian Kingdom. He has recorded 1 of the top Mardi Gras albums of all time, and has recorded some of the most famous Mardi Gras tunes in Carnival history. I met Bo Dollis,Sr. with my client and good friend, June Victory. Bo was sitting on his little scooter, which helps him get around. Bo’s wife runs a salon in Mid City where they give haircuts, etc. Bo hangs around there.

Listen to Handa Wanda Parts 1 & 2 by the Wild Magnolias

Handa Wanda, Pt. 1

Some of the below bio is from wildmagnolias.net

Theodore Emile “Bo” Dollis was born in New Orleans in 1944. His father was from Baton Rouge, and his mother came from a French-speaking Creole family in St. Martinville, Louisiana. Bo grew up in the central city, an old, run-down commercial-residential uptown neighborhood behind the grand St. Charles Avenue mansions. He was first attracted to the African-Caribbean-American tradition of Carnival Indians while still a youngster.

Bo’s career as a performer and his development as one of the classic singers in the history of the New Orleans recording began when, as a junior in high school, he secretly started attending Sunday night Indian “practice” in a friend’s back yard. He followed The White Eagles tribe, playing and singing the traditional repertoire. In 1957 he masked for the first time with The Golden Arrows, not telling his family of his involvement with the Indians. He made his suit at someone else’s house and told his folks he was going to a parade. Hours later his father discovered him, having recognized his son in the street, underneath a crown of feathers.

Bo Dollis’ name is virtually synonymous with the Wild Magnolias Mardi Gras Indian Tribe. He is clearly the most popular Indian Chief (chosen in 1964) in New Orleans, with everybody wanting to see him in his hand-crafted suit on Mardi Gras or St. Joseph’s Day. Bo has been a legend almost from the beginning, because he could improvise well and sing with a voice as sweet as Sam Cookie, but rough and streetwise, with an edge that comes from barroom jam sessions and leading hundreds of second-lining dancers through the streets at Carnival time.

In 1974 they released the legendary Wild Magnolias album, backed by a New Orleans all-star band that included Willie Tee, his brother Earl Turbinton, Jr. on saxophone, Snooks Eaglin on guitar and Alfred “Uganda” Roberts on percussion. This band’s performance at the Bottom Line in New York made the Magnolias headline news.

In 1975, Dollis and Monk Boudreaux, Chief of the Golden Eagles, recorded James “Sugarboy” Crawford’s 1954 R&B hit Jackomo, Jackomo. There is contrast in their vocal phrasing, and each swings the story line at a slightly different pace; nonetheless, the unity of spirit shines through. You can hear the closeness of these two childhood friends, the only two professional Chiefs performing in New Orleans. In 1970, they appeared at the first New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. Shortly afterward, they collaborated on the classic Mardi Gras song Handa Wanda. Seldom do they sing together in practice.

The Wild Magnolias and The Golden Eagles have taken Bo Dollis and Monk Boudreaux from the ghettos and brought them to places like Carnegie Hall in New York City, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, DC, London, Nice and Berlin. Where ever they go, listeners will hear an authentic music to which New Orleans owes so much.

In the 1980’s, June Victory joined the Wild Magnolias as lead guitarist. On the Mardi Gras Indians Super Sunday Showdown CD (Rounder, 1992), June has 2 arrangements, Oops Upside Your Head & Battlefront. After June Victory left the Magnolias, June Yamagishi took his place.

In January 2009, Bo Dollis received the Best of the Beat Lifetime Achievement Award from OffBeat Magazine. OffBeat contributor John Swenson interviewed Bo about his life and art:

Were your parents music fans?

No.

So did you listen to the radio growing up? Jazz, R&B?

No.

Gospel?

Yeah. I did sing in church. Everybody went to church, my mama and brothers went. It was just singing. I didn’t think anything of it. I would sing with the choir at church. We sang around the house. People would come to hear me sing.

I can’t say it like I wish I could anymore. I sang… what’s his name? Fats Domino! I wanted to be like him. People would say, “He sounds just like Fats Domino.”

You got introduced to the Indians by a neighbor, right?

The Indians were what I was interested in. He was an Indian chief and he was right there where I lived and I used to watch him make an Indian suit. He was with the White Eagles and I used to watch him. He’d give me little pieces and I tried to make one myself. So I made my first Indian suit. I ended up with the Wild Magnolias. I went with the White Eagles but they had a Big Chief and I could only be a Red Indian with them so I left. So I ended up with the Wild Magnolias because there I got a spot. I got with them and I got to be a Flag Boy. I’ve been with them ever since.

You must have been a hell of a Flag Boy because you moved up to Big Chief pretty quickly.

I had a good voice and they wanted me to sing. With the White Eagles I couldn’t sing. See the Indians can’t sing. They can answer, but they can’t sing. We walk down the street and I sing [amazingly, his voice opens up to full strength as he sings a patois that ends with “Down the street here I come”].

You put on a suit. You look good. I was… young. They say they want me to be chief, and some of the people in there were 35, 55. I said, “I don’t wanna be no Big Chief,” and everybody said, “You’re good! You gotta sing. You’re Big Chief.”

I wanted to be the Spy Boy. I was young and I could move around. I wanted to spy out on the other tribes.

Did you start writing songs for the Indians right away?

I would sing, and what you hear Indians sing today is what I was singing then. You don’t hear too many of the new Indians singing the older songs, but it’s more of the stuff that I used to do. They don’t know the words to the songs. They may know the title, but they don’t know the words to the song. They don’t know what they’re doing. They not Mardi Gras Indians they just talkin’… they just crazy.

When you started out, were the old timers then doing different songs or different lyrics to songs?

Maybe one or two guys, but they all sang the same songs.

It was a ritual.

Right. But they don’t have that now. They don’t know that.

So you think some of that ritual is lost.

Oh yeah. All that’s lost. They don’t try. There’s no more Indians

When you were coming up, you were part of a whole generation of young people who were becoming Indians, right?

Yeah. We were young. One time with the Indians you could go from up here to the Treme and back, marching. Now you can’t go from here to up the block because the suits are too big. [laughs] They got to be carried on a cart because the suits are too big for the people, too heavy. It’s pretty…

In the old days you traveled light because you had to cover a lot of distance.

Right. All except the chief, he always had the suit.

Gerard: Back then, the other Indians except the Chief, the Second Chief, the Trail Chief, the Spy Boy and all, they might wear four or five patches. Now they wear 20 patches.

Dollis: Everybody wants to be chief. [laughs]

Gerard: You know that Flag Boy might have a flag in his hand, the Wild Man might be carrying a wooden shotgun, that’s how you tell who they are. The Chief is supposed to have the biggest crown, that’s how you tell who he is. Today you might see some Flag Boy with a bigger crown than the Chief! When I started out, you had five, six patches. Now I’ve been doing it a while so I got 20 patches, but nobody starts with five or six patches now. Now I don’t think anybody want to be an Indian except for the Wild Man.

Was it a difficult decision to record the Mardi Gras Indian music, which was considered a secret ritual up to that time?

No, no, no. I was all for it. I always loved to sing. Quint came to an Indian practice. I didn’t know if I could stay in tune. I never wrote music but I could sing. Whatever the band played, I could sing it. Anywhere you go, I could go. I can’t write music, but I can feel whatever they do.

Gerard: Quint came to an Indian practice, he didn’t know who my dad was. My dad came in and started singing and Quint was like, “Whoa, who’s this voice? We’re going to put you in the studio.” So he just started singing.

This was 1970, which was also the first year of jazz festival.

Yeah. We led the first parade. Me and Monk. I put my suit on and started singing, leading a second line, down Canal Street all through the French Quarter, singing all the way to Congo Square and the people followed along all the way. I was singing. With all the other Indians.

That was the year you opened up Mardi Gras Indian culture to a whole new audience.

Gerard: A lot of people were scared of the Indians back in those days. They heard about all the violence, so they were more scared than anything else.

Dollis: We tell about the days way back they was wild, wild, wild; I mean they was cutting, killing and shooting. The uptown and the downtown would fight. We didn’t want that. So we stopped. Tootie Montana was big on that. He wanted to get it straight because he was beautiful. He looked so good. Then everybody wanted to be… beautiful. So we got all the Indians and all the chiefs to stop the violence.

Gerard: We all just wanted to change it. We fought with pretty suits instead of our hands and knives and guns. Back in the old days we’d fight in the day then at night we’d buy each other drinks in the bar. But when it comes to guns, there’s no buying drinks after the fight. Once the guns come out, you’re either going to jail or you’ll be six feet under.

Dollis: The gangs today, they kind of like looking like those old Indians were with the way they fight and shoot.

Maybe they can stop the violence again like you guys did.

They won’t until they can find somebody to lead them there. They need a chief to take care of it.

Were you close with Tootie Montana?

I was friends with Tootie, but I didn’t see him so much. I would see him at Jazz Fest or Mardi Gras day or Super Sunday. He knew me and I knew him. We both loved what we do.

When you would meet Tootie or another chief on the street during Mardi Gras, you had a ritual exchange. Did you really try to get the upper hand or was everybody cool about it?

The people wanted to see us confront each other and yell and sing or something like that, but we knew each other and what to do. A lot of times it was about your suit and showing that off. I used to try and see the other chief’s suit before he sees me. I used to try and see them before they come out of their house. One time, I went to a house to look and his crown was so big he couldn’t get out his front door! That’s how big some of them got.

After Katrina a lot of the neighborhoods are gone and not as many Mardi Gras Indians are around. Do you think it will ever come back to what it once was?

Since the storm… everybody now… tryin’… it’s only for money. Ain’t nobody….

But surely some of the Indians are keeping it alive.

Yeah, they’re keeping it alive, but nobody knows what they should be doing. What I wanted to do, I wanted somebody to talk to all the Indians, all over the city and write a book. So we could have all that information documented. I got nobody who could do it. ’Cause you can’t even find all the Indians I know about. I could talk to them myself, I know how to talk to them. I wanted the older people to tell about it. I wanted to get that done. But now I can’t… talk.

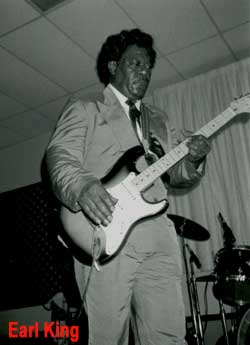

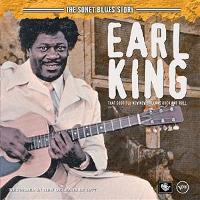

Mardi Gras Music Series: EARL KING

0I’ve been a big fan of Earl King since moving to New Orleans in the middle 1970’s. I remember seeing Earl at the Jazz Fest in the late 1970’s. He was a true R&B powerhouse. I purchased a copy of the Trick Bag album, it was 1 of the top 5 New Orleans R & B tunes for me, along with Tell It Like It Is, Go To The Mardi Gras, Cha Dookie-Doo, and Mardi Gras Mambo.

Unilaterally respected around his Crescent City birthplace as both a performer and a songwriter, guitarist Earl King was a leading New Orleans R&B force for more than 4 decades.

Mardi Gras tune- Street Parade by Earl King

Born Earl Johnson, the youngster considered the catalogs of Texas guitarists T-Bone Walker and Gatemouth Brown almost as fascinating as the live performances of local luminaries Smiley Lewis and Tuts Washington. King met his major influence and mentor, Guitar Slim, at the Club Tiajuana, one of King’s favorite haunts (along with the Dew Drop, of course). The two instantly became friends. Still performing under the name Earl Johnson, the guitarist debuted on wax in 1953 on Savoy with “Have You Gone Crazy.” On this record, longtime pal Huey “Piano” Smith made the first of his many memorable supporting appearances.

In the world of the Blues the name of “King” is highly respected. Most fans associate the surname with the obvious “Big 3,” Albert, B.B. and Freddie. But in New Orleans, the residents know there is a 4th that deserves his place alongside these 3: Earl King.

Earl King was more than just a musician. He was a renaissance man. During his nearly 5 decade career, he wore many hats: guitarist, vocalist, songwriter, producer, sideman, arranger and mentor. He was prolific in his output, perhaps only rivaled by Allen Toussaint for recognizable material. His songs have been covered by the likes of Fats Domino, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan, The Meters, Johnny Adams, Professor Longhair and many more. And unlike many other artists of his generation, he profited from the royalties gained by those who covered his songs as he had wisely retained the copyrights to his work.

He was born in New Orleans as Earl Silas Johnson on February 6, 1934. Raised in the city’s Irish Channel neighborhood, his father was a Blues pianist who was a close acquaintance with the locally renowned Tuts Washington. But Earl’s father died when he was still quite young and he was raised in a single-parent home by his mother, a heavy-set woman known affectionately as “Big Chief.”

Earl’s musical life began in the family church. He participated in the choir singing Gospel. But one day while walking through the neighborhood he heard the guitar playing of Smiley Lewis emanating from a bar. The music enchanted him and he sought means to express his singing outside of the church.

Pianist Huey Smith heard the teenager sing and decided to hire him for his band. Needing another vocalist and musician, he convinced Earl to pick up the guitar.

Johnson became Earl King upon signing with Specialty the next year. Label head Art Rupe intended to name him King Earl, but the typesetter accidentally reversed the names. A Mother’s Love, King’s first Specialty offering, was an especially accurate Guitar Slim homage produced by Johnny Vincent, who would soon launch his own label, Ace Records, with King one of his principal artists. King’s first Ace single, the seminal two-chord south Louisiana blues Those Lonely, Lonely Nights, proved a national R&B hit (despite a sound-alike cover by Johnny “Guitar” Watson). Smith’s rolling piano undoubtedly helped make the track a hit.

I notice this Trick Bag album is on the Sonet label, that’s a Scandinavian label, I knew the owners, and did business with the Storyville label for many years. It was sold to Polygram and for a decade they buried the label.

King remained with Ace throughout the rest of the decade, recording an unbroken string of great New Orleans R&B sides with the unparalleled house band at Cosimo’s studio. He later moved to Imperial to work with producer Dave Bartholomew in 1960, cutting the classic Come On (also known as Let The Good Times Roll) and 1961’s humorous Trick Bag. He managed a second chart item in 1962 with Always a First Time. King wrote standout tunes for Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, and Lee Dorsey during the 1960s.

Although a potential 1963 pact with Motown was scuttled at the last moment, King admirably rode out the rough spots during the late ’60s and ’70s. In the 1990s, he rejuvenated his career by signing with Black Top; Sexual Telepathy and Hard River to Cross were both superlative albums.After releasing well over 100 albums, the label folded in 1999. Nauman Scott died in 2002. Hammond Scott sold the rights of the catalog, and some releases were reissued on labels such as Varèse Sarabande, Fuel 2000 and Shout! Factory. In 2006, P-Vine Records in Japan acquired the worldwide rights to them, and has reissued a few of the CD’s from the catalog.

In 2001, King was hospitalized for an illness during a tour to New Zealand, however, that did not stop him from performing. In December of the same year, he toured Japan, and he continued to perform off and on locally in New Orleans until his death.

He died on April 17, 2003, from diabetes related complications, just a week before the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. His funeral was held during the Festival period on April 30, and many musicians including Dr. John, Leo Nocentelli and Aaron Neville were in attendance.[4] His Imperial recordings, which have been long out-of-print, were reissued on CD soon after he died. The June 2003 issue of a local music magazine OffBeat paid a tribute to King by doing a series of special articles on him.

Mardi Gras Music Series- NEVILLES BROTHERS BAND

0I interviewed Art and Aaron for an earlier MG publication a couple of decades ago. I remember the very first time I heard Aaron sing Tell It Like It Is live- my jaw dropped!! It was the most beautiful song I had ever heard. I’ve been a fan of the Nevilles since they formed the family band in 1976. I remember seeing the Nevilles the year they first appeared at the Jazz Fest as the Neville Bros. That year, the original Meters also appeared, with new recruits taking Art and Cyril’s places. What was remarkable about both appearances was each group played the exact same sets!!

Art and Aaron Neville are as well known as any R&B performers in New Orleans, and have been able to attract large audiences for over 45 years both separately and together. Since 1976, with their brothers Cyril and Charles they have been performing as the Neville Brothers Band, drawing big crowds both in town and on their various tours.They have played such cities as New York, San Francisco, Chicago and Los Angeles as well as in Europe and Asia; and have opened for the Rolling Stones several times during their many tours.

The Neville family influence on R&B music began with George Landry and continues with Ivan (Aaron’s son) & Ian Neville (Art’s son). Cyril Nevile was a member of the Meters during the group’s later years and Charles wrote the music for Shangri-La, a musical that enjoyed several New Orleans runs.

Aaron has recorded such beautiful ballads as Arianne and Tell It Like It Is, which was a regional hit in 1964 and helped to establish his career. Aaron recorded several Grammy winning, platinum albums with Linda Ronstadt, and also several national TV commercials for major companies. He has been described by many music lovers and critics as having one of the sweetest voices performing today.

Art Neville started with the Hawkettes as a teenager and while most of the band was in high school they recorded Mardi Gras Mambo (1954) which instantly became, and still is, a Carnival classic. They Hawkettes were a popular New Orleans group as were the Meters, with whom Art helped found and play with until the Neville’s family band was formed.

Above, an incredible performance of Tell It Like It Is sung by Aaron Neville, Bonnie Raitt,and Greg Allman.

Back in 1979, when NOPD went on strike during Carnival and the Orleans parades were canceled, my family and entourage had to switch plans for Mardi Gras Day. Instead of Zulu, Rex and the trucks, we went for the Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indians in our neighborhood. There was Aaron and Charles Neville with their uncle George Landry and Norman Bell, Chief and Second Chief of the Wild Tchoupitoulas. We smoked a funny cigarette with Aaron while marching around the uptown neighborhood. It was very memorable and a excellent substitute for Zulu and Rex.

Q. How did you celebrate Mardi Gras growing up, and today?

Art: On the big day everyone masked back then. If then didn’t have the money, they used anything they had, such as bottle tops and corks- people would have them stuck all over. Now, around Carnival time, we play a lot of music, and I like that. I used to go to the parades, but now I don’t – I watch them on TV. I still go out and walk around a little, I like to watch the trucks, but the parades seem all the same, they don’t change.

Aaron: The Indians were my favorite part of the Mardi Gras when I was growing up, I followed them but I had no patience to sew a costume. Today, I don’t usually go far from home, I manage without that. All the parades pass by near my house, then I come home and each my red beans and hot dogs, and watch the rest on TV. I leave downtown to the visitors.

Q. Can you describe the influence your late uncle, Chief Jolly (George Landry), has had on your music?

Art: He’s a big part of the Neville family tradition. It’s been passed down to us from all our family. Jolly was my mother’s youngest brother, we dedicated one of our albums to him. He had his own style, he was close to the piano.

Aaron: Chief Jolly started the Wild Tchoupitoulas Indians in the mid 1970’s. He’d been with several other tribes throughout his life. I used to watch him sewing his costume on and off all year. If Jolly was alive today, we’d still be doing the Wild Tchoupitoulas with him. The Indian songs we still do today were done by him. Our mother, she and Jolly had a dance team when they were young, Jolly stayed at the piano while Mother danced. His style was similar to Professor Longhair’s, but his own.

Q. Do any members of the Neville family still put on Indian costumes?

Art: People in New Orleans don’t want to see that most of the year, except around Carnival time. On the road, very few have seen the Indians and it’s extremely effective, it works and there’s no denying it.

Aaron: I don’t put on a costume anymore, neither does Art. I have though, at one time all of us did. The Indian outfits are very hot and heavy, especially after playing a whole set as the Neville Brothers. In the past, it’s been the Neville children who dress up in the costumes – Aaron Jr., my nephew Derrick, Charlie’s daughter Charmaine, they carry on the stage tradition. On the street, on Mardi Gras, we don’t really participate much anymore, but out of town it’s been part of our stage show in the past.

About Meet de Boys in the Battlefront,

Written by Big Chief Jolly (George Landry), Meet De Boys On The Battlefront is an interesting expression of the Mardi Gras Indian tradition. Boasting about their beautiful handcrafted suits and fighting spirit, his song tells of taking to the streets Mardi Gras morning to have “fun”, displaying, singing cryptic chants, drinking, and doing battle on the holiday. Of course, over the past 40 years or so, their battles have become ritualized public competition to see who has created the best regalia and shows out best on the streets, rather than the sometimes violent gang-style turf fights (using shanks, axes, and even guns) that kept the Indians underground and outside the law for many years earlier in the 20th century.

From the Wild Tchoupitoulas Album, a nice youtube video-

Aaron singing Tell It Like It Is in England with the Neville Brothers

Mardi Gras Music Series- AL “CARNIVAL TIME” JOHNSON

1Al Johnson is a living NOLA legend, a real old fashioned gentlemen, and a fun guy to this day. Katrina hurt Al, like many business dealings have, but he’s a born optimist and a real booster of the Crescent City. I know Al, he’s a fairly quiet, handsome guy with a magnetic smile.

From- alcarnivaltimejohnson.com:

![]()

IT’S CARNIVAL TIME AND EVERYBODY’S HAVIN’ FUN !

Alvin Lee Johnson is better known to everyone in New Orleans as Al “Carnival Time” Johnson. His famous song, “Carnival Time,” dates back to February 1960. The original recording was done at Cosimo Matassa’s recording studio by record producer Joe Ruffino on the Ric Label. There have been numerous releases of “Carnival Time” on compilation albums, cassettes, and CD’s over the last forty years. “Carnival Time” has made it to the Mellennium, now with the sole rights belonging to Al Johnson. Al fought to obtain the legal rights to his wonderfully famous song, but the song did not make him wealthy. With his good spirits and humble attitude, Al Johnson is eager to write and produce new songs. Al Johnson is now in the forefront awaiting his reowned popularity.

Alvin Lee Johnson is better known to everyone in New Orleans as Al “Carnival Time” Johnson. His famous song, “Carnival Time,” dates back to February 1960. The original recording was done at Cosimo Matassa’s recording studio by record producer Joe Ruffino on the Ric Label. There have been numerous releases of “Carnival Time” on compilation albums, cassettes, and CD’s over the last forty years. “Carnival Time” has made it to the Mellennium, now with the sole rights belonging to Al Johnson. Al fought to obtain the legal rights to his wonderfully famous song, but the song did not make him wealthy. With his good spirits and humble attitude, Al Johnson is eager to write and produce new songs. Al Johnson is now in the forefront awaiting his reowned popularity.

“Carnival Time” was an inspiration to Al Johnson from fellow musicians such as Professor Longhair’s “Go To The Mardi Gras,” and Lou Welch’s “Mardi Gras Mambo.” Al Johnson wanted a song the locals of New Orleans could relate to on Mardi Gras Day. With lyrics “the Green Room is smoking” and “the Plaza’s burning down,” were real places the locals knew about. Almost everyone in New Orleans at one time has referred to Mardi Gras as “Carnival Day.”

“Carnival Time” is definitely a song that when it hits the air waves, one can hardly resist the real Mardi Gras groove. “Carnival Time” with its intoxicating rhythm and its fun to sing lyrics has always been a big musical hit in New Orleans since its release in 1960. Before, during and after Al Johnson’s legal battles for his song “Carnival Time,” the song continued to be performed and enjoyed by its listeners every Mardi Gras/ Carnival Time season.

“Carnival Time” is definitely a song that when it hits the air waves, one can hardly resist the real Mardi Gras groove. “Carnival Time” with its intoxicating rhythm and its fun to sing lyrics has always been a big musical hit in New Orleans since its release in 1960. Before, during and after Al Johnson’s legal battles for his song “Carnival Time,” the song continued to be performed and enjoyed by its listeners every Mardi Gras/ Carnival Time season.

Al Johnson has released his own CD single with the original version of “Carnival Time” and newly recorded “Mardi Gras Strut.” “Mardi Gras Strut” offers the listener a tune to “get down and strut.” Special assistance from Earline Hutchison helped Al Johnson to obtain that sound he was searching for in this newly recorded CD single. “Mardi Gras Strut” not only presents a good groove but also gives the listeners identifiable lyrics which is at the heart of Al Johnson’s writing. Al Johnson’s love for his city and the Mardi Gras season is definitely recognized in “Carnival Time” and “Mardi Gras Strut.”

Al Johnson has released his own CD single with the original version of “Carnival Time” and newly recorded “Mardi Gras Strut.” “Mardi Gras Strut” offers the listener a tune to “get down and strut.” Special assistance from Earline Hutchison helped Al Johnson to obtain that sound he was searching for in this newly recorded CD single. “Mardi Gras Strut” not only presents a good groove but also gives the listeners identifiable lyrics which is at the heart of Al Johnson’s writing. Al Johnson’s love for his city and the Mardi Gras season is definitely recognized in “Carnival Time” and “Mardi Gras Strut.”

Listen to Carnival Time