New Orleans Carnival

Mardi Gras Music Series- NEVILLES BROTHERS BAND

0I interviewed Art and Aaron for an earlier MG publication a couple of decades ago. I remember the very first time I heard Aaron sing Tell It Like It Is live- my jaw dropped!! It was the most beautiful song I had ever heard. I’ve been a fan of the Nevilles since they formed the family band in 1976. I remember seeing the Nevilles the year they first appeared at the Jazz Fest as the Neville Bros. That year, the original Meters also appeared, with new recruits taking Art and Cyril’s places. What was remarkable about both appearances was each group played the exact same sets!!

Art and Aaron Neville are as well known as any R&B performers in New Orleans, and have been able to attract large audiences for over 45 years both separately and together. Since 1976, with their brothers Cyril and Charles they have been performing as the Neville Brothers Band, drawing big crowds both in town and on their various tours.They have played such cities as New York, San Francisco, Chicago and Los Angeles as well as in Europe and Asia; and have opened for the Rolling Stones several times during their many tours.

The Neville family influence on R&B music began with George Landry and continues with Ivan (Aaron’s son) & Ian Neville (Art’s son). Cyril Nevile was a member of the Meters during the group’s later years and Charles wrote the music for Shangri-La, a musical that enjoyed several New Orleans runs.

Aaron has recorded such beautiful ballads as Arianne and Tell It Like It Is, which was a regional hit in 1964 and helped to establish his career. Aaron recorded several Grammy winning, platinum albums with Linda Ronstadt, and also several national TV commercials for major companies. He has been described by many music lovers and critics as having one of the sweetest voices performing today.

Art Neville started with the Hawkettes as a teenager and while most of the band was in high school they recorded Mardi Gras Mambo (1954) which instantly became, and still is, a Carnival classic. They Hawkettes were a popular New Orleans group as were the Meters, with whom Art helped found and play with until the Neville’s family band was formed.

Above, an incredible performance of Tell It Like It Is sung by Aaron Neville, Bonnie Raitt,and Greg Allman.

Back in 1979, when NOPD went on strike during Carnival and the Orleans parades were canceled, my family and entourage had to switch plans for Mardi Gras Day. Instead of Zulu, Rex and the trucks, we went for the Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indians in our neighborhood. There was Aaron and Charles Neville with their uncle George Landry and Norman Bell, Chief and Second Chief of the Wild Tchoupitoulas. We smoked a funny cigarette with Aaron while marching around the uptown neighborhood. It was very memorable and a excellent substitute for Zulu and Rex.

Q. How did you celebrate Mardi Gras growing up, and today?

Art: On the big day everyone masked back then. If then didn’t have the money, they used anything they had, such as bottle tops and corks- people would have them stuck all over. Now, around Carnival time, we play a lot of music, and I like that. I used to go to the parades, but now I don’t – I watch them on TV. I still go out and walk around a little, I like to watch the trucks, but the parades seem all the same, they don’t change.

Aaron: The Indians were my favorite part of the Mardi Gras when I was growing up, I followed them but I had no patience to sew a costume. Today, I don’t usually go far from home, I manage without that. All the parades pass by near my house, then I come home and each my red beans and hot dogs, and watch the rest on TV. I leave downtown to the visitors.

Q. Can you describe the influence your late uncle, Chief Jolly (George Landry), has had on your music?

Art: He’s a big part of the Neville family tradition. It’s been passed down to us from all our family. Jolly was my mother’s youngest brother, we dedicated one of our albums to him. He had his own style, he was close to the piano.

Aaron: Chief Jolly started the Wild Tchoupitoulas Indians in the mid 1970’s. He’d been with several other tribes throughout his life. I used to watch him sewing his costume on and off all year. If Jolly was alive today, we’d still be doing the Wild Tchoupitoulas with him. The Indian songs we still do today were done by him. Our mother, she and Jolly had a dance team when they were young, Jolly stayed at the piano while Mother danced. His style was similar to Professor Longhair’s, but his own.

Q. Do any members of the Neville family still put on Indian costumes?

Art: People in New Orleans don’t want to see that most of the year, except around Carnival time. On the road, very few have seen the Indians and it’s extremely effective, it works and there’s no denying it.

Aaron: I don’t put on a costume anymore, neither does Art. I have though, at one time all of us did. The Indian outfits are very hot and heavy, especially after playing a whole set as the Neville Brothers. In the past, it’s been the Neville children who dress up in the costumes – Aaron Jr., my nephew Derrick, Charlie’s daughter Charmaine, they carry on the stage tradition. On the street, on Mardi Gras, we don’t really participate much anymore, but out of town it’s been part of our stage show in the past.

About Meet de Boys in the Battlefront,

Written by Big Chief Jolly (George Landry), Meet De Boys On The Battlefront is an interesting expression of the Mardi Gras Indian tradition. Boasting about their beautiful handcrafted suits and fighting spirit, his song tells of taking to the streets Mardi Gras morning to have “fun”, displaying, singing cryptic chants, drinking, and doing battle on the holiday. Of course, over the past 40 years or so, their battles have become ritualized public competition to see who has created the best regalia and shows out best on the streets, rather than the sometimes violent gang-style turf fights (using shanks, axes, and even guns) that kept the Indians underground and outside the law for many years earlier in the 20th century.

From the Wild Tchoupitoulas Album, a nice youtube video-

Aaron singing Tell It Like It Is in England with the Neville Brothers

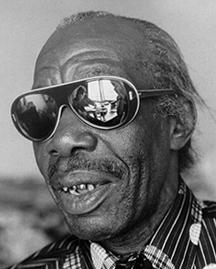

Mardi Gras Music Series- AL “CARNIVAL TIME” JOHNSON

1Al Johnson is a living NOLA legend, a real old fashioned gentlemen, and a fun guy to this day. Katrina hurt Al, like many business dealings have, but he’s a born optimist and a real booster of the Crescent City. I know Al, he’s a fairly quiet, handsome guy with a magnetic smile.

From- alcarnivaltimejohnson.com:

![]()

IT’S CARNIVAL TIME AND EVERYBODY’S HAVIN’ FUN !

Alvin Lee Johnson is better known to everyone in New Orleans as Al “Carnival Time” Johnson. His famous song, “Carnival Time,” dates back to February 1960. The original recording was done at Cosimo Matassa’s recording studio by record producer Joe Ruffino on the Ric Label. There have been numerous releases of “Carnival Time” on compilation albums, cassettes, and CD’s over the last forty years. “Carnival Time” has made it to the Mellennium, now with the sole rights belonging to Al Johnson. Al fought to obtain the legal rights to his wonderfully famous song, but the song did not make him wealthy. With his good spirits and humble attitude, Al Johnson is eager to write and produce new songs. Al Johnson is now in the forefront awaiting his reowned popularity.

Alvin Lee Johnson is better known to everyone in New Orleans as Al “Carnival Time” Johnson. His famous song, “Carnival Time,” dates back to February 1960. The original recording was done at Cosimo Matassa’s recording studio by record producer Joe Ruffino on the Ric Label. There have been numerous releases of “Carnival Time” on compilation albums, cassettes, and CD’s over the last forty years. “Carnival Time” has made it to the Mellennium, now with the sole rights belonging to Al Johnson. Al fought to obtain the legal rights to his wonderfully famous song, but the song did not make him wealthy. With his good spirits and humble attitude, Al Johnson is eager to write and produce new songs. Al Johnson is now in the forefront awaiting his reowned popularity.

“Carnival Time” was an inspiration to Al Johnson from fellow musicians such as Professor Longhair’s “Go To The Mardi Gras,” and Lou Welch’s “Mardi Gras Mambo.” Al Johnson wanted a song the locals of New Orleans could relate to on Mardi Gras Day. With lyrics “the Green Room is smoking” and “the Plaza’s burning down,” were real places the locals knew about. Almost everyone in New Orleans at one time has referred to Mardi Gras as “Carnival Day.”

“Carnival Time” is definitely a song that when it hits the air waves, one can hardly resist the real Mardi Gras groove. “Carnival Time” with its intoxicating rhythm and its fun to sing lyrics has always been a big musical hit in New Orleans since its release in 1960. Before, during and after Al Johnson’s legal battles for his song “Carnival Time,” the song continued to be performed and enjoyed by its listeners every Mardi Gras/ Carnival Time season.

“Carnival Time” is definitely a song that when it hits the air waves, one can hardly resist the real Mardi Gras groove. “Carnival Time” with its intoxicating rhythm and its fun to sing lyrics has always been a big musical hit in New Orleans since its release in 1960. Before, during and after Al Johnson’s legal battles for his song “Carnival Time,” the song continued to be performed and enjoyed by its listeners every Mardi Gras/ Carnival Time season.

Al Johnson has released his own CD single with the original version of “Carnival Time” and newly recorded “Mardi Gras Strut.” “Mardi Gras Strut” offers the listener a tune to “get down and strut.” Special assistance from Earline Hutchison helped Al Johnson to obtain that sound he was searching for in this newly recorded CD single. “Mardi Gras Strut” not only presents a good groove but also gives the listeners identifiable lyrics which is at the heart of Al Johnson’s writing. Al Johnson’s love for his city and the Mardi Gras season is definitely recognized in “Carnival Time” and “Mardi Gras Strut.”

Al Johnson has released his own CD single with the original version of “Carnival Time” and newly recorded “Mardi Gras Strut.” “Mardi Gras Strut” offers the listener a tune to “get down and strut.” Special assistance from Earline Hutchison helped Al Johnson to obtain that sound he was searching for in this newly recorded CD single. “Mardi Gras Strut” not only presents a good groove but also gives the listeners identifiable lyrics which is at the heart of Al Johnson’s writing. Al Johnson’s love for his city and the Mardi Gras season is definitely recognized in “Carnival Time” and “Mardi Gras Strut.”

Listen to Carnival Time

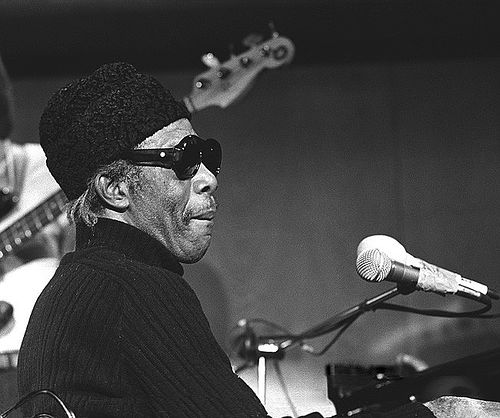

Mardi Gras Music Series- PROFESSOR LONGHAIR

0I’m very very partial to the tunes and Mardi Gras Spirit of Professor Longhair. When I first arrived in NOLA in the mid 70’s, Fess very much alive, and I remember seeing Fess live at Tipitina’s many times. It wasn’t until Longhair had been dead for 15 years that his music really took off. That’s when I got involved in the Longhair estate professionally and made sure his heirs would be properly taken of. I went to the south Riviera of France, to MIDEM, the premier music publishing conference after setting up meetings with international roots publishers I knew. I met with Don Williams (dwmg.com). He owned some great roots music catalogs, but none from New Orleans. He was very interested in the Longhair publishing sale. Within a few years, he purchased Longhair, Booker, and Earl King’s publishing catalogs. All 3 had songs in all 3.5 seasons of Treme, HBO’s series about NOLA after Katrina. The Booker, Earl King and Longhair estate are all thriving financially as they head into 2013.

New Orleans has an exotic flavor all its own, and Professor Longhair exemplifies the colorful music traditions that are representative of the city.

At the time of his death at age 62 he remained a brilliant pianist and singer with an unusual, appealing voice. Fess died a relatively poor man in January 1980. He owned 1 huge asset- the songs he wrote. His will showed his unusually large heart. Fess had 2 kids, a boy and a girl, by his wife Alice. While these kids were growing up, Alice left Fess and had 4 kids with other fathers. These 4 kids were Alice’s, not Fess’, yet he gave 25% of his estate to Alice’s kids, and 75% to his 2 kids. That’s a big man!

His Carnival songs, Big Chief, Parts 1 & 2 and Mardi Gras in New Orleans remain very popular after all these years because they reflect the exuberant spirit of Mardi Gras. Longhair’s songs are related to the second line dance beat popularized by New Orleans Jazz funerals. He described his music as a combination of “rumba, mambo and Calypso.” Born in Bogalusa, Louisiana in 1918, Henry Roeland Byrd’s family moved to New Orleans in the early 1920s. Young Roy first became a proficient tap dancer, then a guitarist, before settling on his voice and piano as his instruments of choice. Dancing outside of taverns for tips as a boy heightened his sense of rhythm.

During the 1930’s, Byrd played the piano professionally while working at other jobs, including the Civilian Conservation Corps, cooking, boxing, and card playing before being drafted in 1942. In the military, Byrd became serious about his playing when he learned he could entertain his fellow Corps workers instead of working. In 1944, he was released from the service due to poor health. Byrd returned to music and around 1947 earned his famous nickname, reminiscent of the old Storyville ‘professors’ who entertained on the piano in the local bordellos. As the story goes, Byrd received his nickname courtesy of the Caldonia Inn’s proprietor, who, upon meeting the long haired Byrd and his group, named them “Professor Longhair and the Four Hairs Combo,” which soon became “Professor Longhair and the Shuffling Hungarians.” Longhair is on record as saying there was a Hindu in the Band, but no Hungarians. 1949 was a big year for the Professor, he recorded his first and most successful songs: She Ain’t Got No Hair, Mardi Gras in New Orleans, Bye Bye Baby, and Professor Longhair’s Boogie. A remake of She Ain’t Got No Hair renamed Baldhead reached number 5 on the Billboard R & B chart during the summer of 1950. He continued to record for several companies sporadically throughout the 1950s. Fess had his biggest Carnival hit when he recorded Mardi Gras in New Orleans as Go to the Mardi Gras, a local hit in 1959. This song sells well every Carnival, but Longhair had no royalty agreement. The Professor recorded a few times in the early and middle 1960’s but again major success and money eluded him. His second Carnival classic, Big Chief, was recorded with Earl King (whistling and on vocals) in 1964. Big Chief was not much of a hit for Longhair himself, although Dr. John revived it in 1972 on his Gumbo album. The Professor’s version, on a 1976 album (featuring twelve R & B Carnival classics by six artists) continues to sell well seasonally and has done much to popularize Big Chief. Music failed to provide Fess with any sort of living during most of the 1960’s, his career didn’t revive until he played at the Louisiana Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1972 and 1973 and the Montreux Festival in Switzerland in 1973. Gloriously, in 1974, the Professor’s career was reborn. He recorded an album, resumed his local club appearances and performed in New York and Europe. In 1975, Tipitina’s, named after one of the Professor’s best songs, opened in uptown New Orleans. Still open, Tip’s is one of New Orleans’ greatest nightclubs today. There’s a beautiful bust of Fess when you first enter the bar. At the end of his life he did achieve some of the recognition he deserved, as rock stars like Paul McCartney came to pay him homage. His last two albums before he passed, Crawfish Fiesta and Mardi Gras in New Orleans, won large critical acclaim and are still available. When he died, he was accorded a traditional jazz funeral, attended by many local music luminaries and thousands of fans (including me!). His unique playing continues to inspire and amaze musicians and fans. Each Carnival, his songs are heard on the radio and on jukeboxes all over town. Fess certainly is missed.

Listen to Fess-

Mardi Gras Indians Seek Copyright Protection For Their Suits

0I’ve met Creole Wild West Chief Howard Miller through my client and good friend, musician June Victory. Chief Howard is a very nice, talented guy who deserves all he can achieve through his art as a Mardi Gras Indian Chief.

Recently he’s filed an online copyright application for his brand new Indian costume in the hopes of collecting some of the income derived from photos, posters, T-Shirts, videos and movies of his costume.

Chief Howard Miller knows cameras will start clicking next month when his Creole Wild West Mardi Gras Indians take to the streets with their elaborately beaded and feathered costumes.

“It’s not about people taking pictures for themselves, but a lot of times people take pictures and sell them,” Miller said.

Intellectual property law dating back to the nation’s founding dictates that apparel and costumes cannot be copyrighted, but Tulane University adjunct law professor Ashlye Keaton has found a way around that by classifying them as something else.

“Their suits and crowns, their regalia, are certainly unique works of art,” Keaton said. “They are entitled to protect that art work.”

Keaton got to know many of the Indians through another Tulane program, the Entertainment Law Legal Assistance Project.

She was intrigued by their art, more so after she saw photos sold at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival and at local galleries, apparently without their permission. Pictures of the Indians sell online for up to $500 each, and books and T-shirts are also available.

Now they and members of the city’s other tribes are working to get a slice of the profits when photos of the towering outfits they have spent the year crafting end up in books and on posters and T-shirts.

Once the costumes are copyrighted, which can be done online for $40, the Indians can either sue people who sell photos of them or try to negotiate licensing fees with photographers either before or after the pictures are taken.

“It’s not about people taking pictures for themselves, but a lot of times people take pictures and sell them,” Miller said.

“For years people have been reaping the benefits from the pictures they take of the Mardi Gras Indians.”

Intellectual property law dating back to the nation’s founding dictates that apparel and costumes cannot be copyrighted, but Tulane University adjunct law professor Ashlye Keaton has found a way around that by classifying them as something else- as works of art.

The first test for the Indians who have copyrighted the new costumes they will wear this year will come at Mardi Gras. The Indians revamp or completely remake their suits every year, and the copyright takes effect at the first public showing, said Ryan Vacca, an assistant professor of law at the University of Akron School of Law.

Once the costumes are copyrighted, which can be done online for $40, the Indians can either sue people who sell photos of them or try to negotiate licensing fees with photographers either before or after the pictures are taken.

“They would be in a good position to negotiate a flat fee or percentage of the sale, something like that,” said Vacca said.

The Mardi Gras Indians have a long and colorful history in New Orleans. Since the end of the 19th century, black men have been making their own version of Indian dress and banding together for informal street parading at Mardi Gras. Local lore holds the tradition sprouted from runaway slaves’ admiration for Native Americans who harbored them from slave hunters before the Civil War.

Mostly the Mardi Gras Indians come from working-class neighborhoods, so their costume investment can take up much of their disposable income.

There is no accurate count of the groups, but about 35 are believed active, many with colorful names such as the Wild Tchoupitoulas, Black Seminoles, Golden Arrows, Wild Magnolias, Fi-Yi-Yi, 7th Ward Hard Head Hunters Golden Blades and Creole Osceola. Each is led by a chief.

Each Indian makes a new suit every year, and over the decades they have become much more glitzy and elaborate. Some cost thousands of dollars.

“It takes the whole year to get ready for Mardi Gras,” Miller said. “I can’t tell you how many hours I put in.”

Miller copyrighted his costume at Keaton’s urging, but it’s unclear how many other Mardi Gras Indians have, since the process has only recently been available online and tracking the old applications is difficult. Miller said he expects many more Indians to copyright their work now that several have done it and can provide help.

He hopes having the copyright will be enough and he will be able to negotiate with photographers and others using his image, rather than sue.

“This is art, what we do,” Miller said. “These suits cost thousands of dollars and all we want is a little bit of what other people make from them.”