Mardi Gras

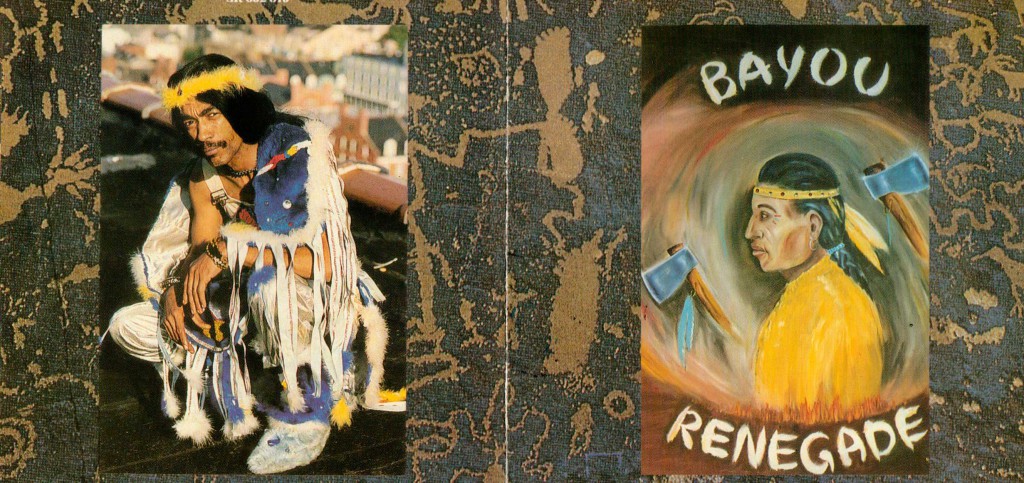

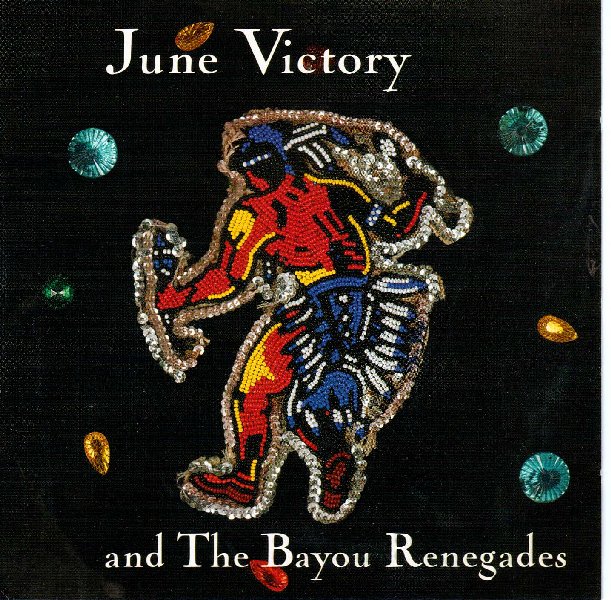

Mardi Gras Music Series- JUNE VICTORY & THE BAYOU RENEGADES

8June is a personal friend, client, and much more. I know most of his big family and we help each other out all the time. He is one of the most talented NOLA guitarists around, yet his persona is more underground than most. He has no CDs in print, his music isn’t available legally online, and he plays only the most chitlin’ circuit clubs around New Orleans.

June’s guitar style is all NOLA- part Hendrix, part Mardi Gras Indian, & part NOLA Funkster. He writes his own music & lyrics, arranges his songs & all instrumentation, produces his own songs and leads his band.

June Victory & Bayou Renegades Song Selection:

Some Press Clips About June Victory

One of the most important records to come out of New Orleans this decade…the real deal…a hell of a guitar player.

CMJ

…like Jimi Hendrix jamming with the Meters.

…The Times-Picayune

Guitarist Victory and the Bayou Renegades have a distinctly 70’s funk sound, drawing as much influence from Sly and the Family Stone and Funkedelic as much as the Mardi Gras Indian tribes. It’s as a funk record that this release really scores.

…OffBeat Magazine

Victory burns with his seductive guitar work which is at once minimal and intricate. His soloing throughout the album is so tasty, and most important lacks the excessiveness that hampers so may other guitarists. June Victory overflows with talent and deserves greater recognition.

…Gambit Weekly

********************

WILSON VICTORIAN (JUNE VICTORY) BIOGRAPHY

Wilson Victorian was born in 1949 in New Orleans, LA. At the age of 8, he went to Houston to attend the Houston Music School and was taught by Walter Epps. He stayed at the school until age 11, when he returned to New Orleans. June was a musical prodigy.

In the 60s, June recorded his first tune at Tracy Knight’s Studio on Metairie Road. One More Silver Dollar was his first recording. This tune became Midnight Rider by the Allman Brothers Band. By the mid 60s, he formed his first band, the Optimistic Band. He appeared on WGSO-TV’s live music program with George Benet.

Around this time, June’s Optimistic Band was opening for Chris Kenner, who was riding high on the back of the Sea Saint produced I Like It Like That, Something You Got, and The Land of 1000 Dances. Chris had a real drinking problem, and liked to pre load up on booze before each gig. His driver was Leroy Bates. One time when June was riding with Chris while Leroy was driving, Leroy reached his limit with Chris’ over drinking problem. He screeched the car to a halt, sending Chris forward in the back seat. Leroy grabbed Chris’ bottle of booze, and threw it out the car window. He turned around to Chris and screamed, “I’ve had it with your drinking, and you’re too drunk at your shows!

In the early 70s, he landed at the 809 Club on Bourbon Street at Chris Owens Club with the Mike Christopher Group. He stayed 3 years, gaining major Bourbon Street chops.

June formed the Bayou Band, and backed up Pure Ice, and appeared with McFadden & Whitehead. They had a regional hit, Live & Let Live. He toured throughout Cajun Country, performed with OV Wright and Jackie Wilson, and became the backup band for Sea Saint Studio.

June’s Bayou Band became Sea Saint’s house band, and he backed up a number of artists, including Tony Owens and Leroy Bates. He recorded Down on the Bayou at Back Street Studio, then at Sea Saint Studio.

Also in the 70s, June created his own outdoor concert setting at Phillip and LaSalle Streets, called Cabbage Alley. He built a set of concrete bleachers for seating, which are still there today. He met Monk Boudreaux and Bo Dollis at Cabbage Alley, and both became big fans of the house band, June’s Bayou Band.

June headed to Tennessee where he met William Johnson. He rented a rehearsal spot from ABC Rental in Tennessee. June signed a contact with Johnson, but the Bayou Band had some personnel problems. June regrouped and left town, touring in Arkansas, Georgia, and Tennessee.

June returns to New Orleans and the Bayou Band is kept busy around town with bookings. They favored the Sabou Club near Bayou St. John, and played featured all original tunes. Soon the band was back on the road. When they returned, they worked at the Parisian Club at Jackson and Dryades Streets. The club wasn’t doing well, and the Bayou Band built a large following which saved the club. June felt the club owner wasn’t paying the band properly, a shoot out ensued, and he took his money back. June went to jail for attempted murder and armed robbery.

In the early 80s, June became burnt out and left the music business and opened a construction company. He married and for three years made very good money, and planned his reentry into the music industry.

However, his best laid plans fizzled mightily and June was arrested for drug dealing out West. He met Philip Rose, a gypsy, in jail, and learned the mud jacking business from him. He hooked June up with the hydraulic equipment needed in the mud jacking business. He met Bill Gillem, the inventor of screw piling, and formed a new construction partnership with Bill. Gillem was a great idea developer but lousy businessman and the partnership fizzled. June had an opportunity to sell trucks via his strong contacts in the construction field. This continued for several years.

Via his many relationships in the entertainment business, June started buying poker machines from New York and installing them throughout Jefferson Parish. The government took notice and got involved. Also at this time, the Feds became interested in June’s construction company, and became partners with him. June did an album with Parisian Philippe Le Bras’ Sky Ranch label and Virgin Records while his construction and gambling companies thrived.

Meanwhile, he got involved in the drug trade.

Unfortunately, June’s partner Charlie was a snitch for the Feds, and when June refused to snitch, Charlie’s participation led to June’s arrest. June had sold drugs to Federal undercover agents and he was caught with 5 guns and marked money. He received a 30 year sentence.

Behind the scenes in Court, things were lining up in June’s favor. His attorney called, offering a very unusual deal: Get back in music, and he could walk away from all charges! June called his old friend and fellow musician, Milton Batiste of the Olympia Brass Band, for a record deal, and the drug and gun charges vanished into thin air.

While all this drama was unfolding, June was busy re-developing his musical style. Norwood Johnson, aka Geegie, a bass player in June’s Bayou Band in the 70s and 80s, remained with the group, and Earl Nunez was brought to play bass drum. The new band configuration was a power trio June named the Power Pack.

Another condition of June’s legal deal was he had to leave Louisiana for a while as a working musician. At 7 am on a Wednesday, June left with the Wild Magnolias, traveling to Minnesota. His band was the “3 Man Crew”. The club was featuring Tracy Chapman, who was in her prime at this time.

June’s new Power Pack band had a funk/Mardi Gras Indian/Psychedelic sound. June had a very good relationship with the club owner so he stayed in Minnesota for a while earning $700/day. He remained in the Wild Magnolias as guitarist. Manager Allison Minor had lined up a record deal in France, so June left Minnesota with Allison for France even though the Minnesota club still wanted June’s services.

Next, Japan beckoned, specifically the Tokyo Roof Club in Tokyo and other clubs in Osaka. Michael Murphy Productions and House of Blues founder Isaac Tigrett sponsored Guitar Battle featuring June, New Orleanian John Mooney, and Japanese funk guitarist June Yamagishi. Mooney performed, and then Yamagishi arrived to back up Mooney. However, Mooney was beaten by Yamagishi. June Victory took up the challenge with Yamagishi, as he wanted to defend Mooney, another American.

Among the Americans involved in this Guitar Battle was Rounder Records, and the PR guy for Michael Jackson. Over breakfast the next morning, the 2 Junes discussed the night before. When June Victory was playing, Yamagishi’s styles conflicted. Yamagishi stopped playing, and Victory began playing solo. He developed a deep rhythm and built a guitar based trance. The deep rhythm wasn’t static, but slipping and sliding. The Japanese audience screamed their approval. Backstage, Mooney gave Victory a big hug, and the two become fast friends. Yamagishi expresses his desire to move to New Orleans.

June returns to New Orleans, and is put under house arrest. Bass drummer and band member Earl Nunez was assigned to June in Louisiana, as the Court’s conditional house arrest allowed June outside with a chaperone. June freed Earl and hired good friend and fellow guitar slinger Ernie Vincent, composer of funk classic “Dap Walk” to chaperone. Ernie has always been drug free, which kept away from the drug trade. As with many talented musicians, June has found that drugs or booze hurt his performance, rather than improve it.

As the 90s dawned, June cut the Mardi Gras Indians Super Sunday Showdown with the Wild Magnolias on Rounder Records. The album features Monk Boudreaux & the Golden Eagles, ReBirth Brass Band, Dr. John, Willie Tee, Champion Jack Dupree, John Mooney and Earl Turbinton, Jr., along with Bo Dollis & the Wild Magnolias. The Magnolias’ two tunes on the disc are June’s arrangement- Oops Upside Your Head and Battlefront.

At this time, Rounder Records pursued the Bayou Renegades to sign with them. However the Magnolias had a conflict with Rounder, so the deal stalled. June hired Yamagishi to learn the Magnolias’ material. For a while, the Magnolias featured both Junes on guitar. Yamagishi’s 1994 album Smokin’ Hole (BMG Victor) featured June Victory.

Music and Entertainment attorney Ellis Pailet entered the scene to help the Bayou Renegades obtain convention gigs. June found time to study the law with Ellis as well. Mary Ann McGrath Swaim befriended June, leading to a tour of France with the Sky Ranch label. Mary Duval surfaced with an entertainment company in New Orleans, and took the Magnolias to California.

At this time, June’s relationship with the Wild Magnolias was suffering. Bo Dollis remained June’s ally, but Monk Boudreaux wasn’t. Manager Allison Miner died in 1995 and Glenn Gaines appears. June’s unique Power Pack Trio sound is out and a big band sound with horns and keyboards takes over.

While June’s relationship with the Magnolias suffered, other relationships strengthened. Local anesthesiologist and vinyl junkie Ira “Dr. Ike” Padnos, a huge fan of June’s guitar style and music, hired June to be the house band for the “Big Blue Flop House” a weekly Sunday house party in an uptown home at the corner of Magazine and Soniat Streets. June utilizes his “3 Man Crew” band version to great acclaim.

As word got out about this weekly event, its popularity grew and grew. Ira supplied the booze and location, June supplied the funk, and there was no stopping until the fete outgrew the neighborhood and had to close. Major parking headaches had developed from all the cars who parked to attend that weeks’ “House Party”.

Meanwhile, things are heating up with the Magnolias. Glenn is proving very difficult to work with. The Magnolias are booked at Tipitina’s with the Power Pack Group version of the Magnolias. The Tipitina’s gig falls through, and the House of Blues is booked. The House of Blues show is a big new show for the Magnolias. After a bitter falling out with Glenn, June refuses to rehearse and is fired from the Magnolias. Except for Earl Nunez, Magnolia bass drummer, the entire band walks off. Geechie and Yamagishi perform at the House of Blues gig.

Soon afterwards, Attorney Pailet re-booked the Tipitina’s gig for June’s Bayou Band. June’s conditional release from jail required June to be fired instead of him quitting so he met that condition.

June leaves for France, but is sent home by his French and Japanese labels to pick up his foxy, talented female drummer, Jasmin. The World Trade Center wants an escort for June to make sure he leaves the country so he remains out of jail. He goes to Mexico and returns to a record deal with New Orleans boutique label Monkey Hill. The label seemed to have a great future with this roster- Cowboy Mouth, an up and coming New Orleans band featuring the great drummer Fred LeBlanc; Bill Summers & Summer Heat; former DBs front man Peter Holsapple; the Continental Drifters, an all star band featuring Holsapple, Bangles guitarist Vicky Peterson, and Susan Cowsill. The label was started and owned by two men, Jimmy Ford and Frank Quintini.

Within a few years, Ford leaves the label abruptly. When asked what happened, he said to ask Frank. When Mr. Quintini was queried, he provided no answers. What occurred to June Victory answers a lot.

June’s eponymous studio album on Monkey Hill dropped in 1998. The record garnered some amazing reviews and sold pretty well in America and Europe. Has June made any money from the sales? An occasional $20 bill from Frank was all the payments June has received on that album. To get that $20, June would have to go to Frank and ask for it, as a royalty check was never forthcoming. June never received a statement covering sales and never received a signed contract to enforce the deal.

In 2003, Monkey Hill released a live album, June Victory & the Bayou Renegades Live at Tipitinas. This album wasn’t released as widely as the studio album, and again June had no documentation, received zero statements and was paid an infrequent sawbuck or two.

Fall 2005, Hurricane Katrina hits, June eventually evacuates to his long time girlfriend Ivory’s family house in Minnesota. June takes sick with cancer and beats it, thanks to advanced medicine. After treating June poorly for a decade, who shows up in Minnesota to crash for a couple of years? None other than Frank Quintini! Who wrecks June’s new ride twice, a beautiful Chrysler-Daimler 300 bought in Minnesota? Frank Quintini! Frank only ponies up the $500 deductible twice when June threatens to evict Frank. Quintini pays the $1,000.

Move forward to 2008, when a few New Orleanians approach the Giacona Container Company, makers of Mardi Gras Throw Cups for many top Mardi Gras Krewes, about producing a new type of Mardi Gras Throw, a Music Medallion. It’s a CD with 5 Mardi Gras tunes in a clear case on a bead. Several major Mardi Gras Krewes purchase this novel throw, including Bacchus, Alla, and Thoth, and all the Mardi Gras supply shops crave it as well. 12,000 units are sold in 3 weeks, meaning the future looks very bright for this new throw. June had 4 tunes on the 4 Music Medallions.

Unfortunately, Frank threatens a Federal suit Giacona over June’s songs, even though his nonexistent contact with June lapsed years ago. Giacona is advised by all partners not to pay, and another artist on the CDs, Ernie Vincent, whom Giacona trusts, talks to Giacona, telling him not to settle.

What does Giacona do? He calls his insurance company, who issues a $3,000 check to Frank’s attorneys. That kills the Music Medallion business. Emboldened by this payoff, Frank tells his attorneys to sue the three New Orleanians who approached Giacona with the Music Medallion concept. So even though there’s no contract, and if there was one it would have lapsed years ago, Frank goes ahead and threatens a Federal copyright suit.

June advises Frank not to sue for the reasons stated in this document, but he disregards his former artist. The case goes nowhere, as by this time, Frank’s attorneys, Booth & Booth, now realize that the suit is garbage and Frank is pursuing another case without any merit. The partners agree to pay $300 each to make the case disappear and give Frank a few bucks.

When June joined the Monkey Hill label, it was an up and coming New Orleans label with a strong roster. After Jimmy Ford left, the label went on a quick downward spiral, and soon the only act still on board was June Victory. Why? June is a very loyal person, and he wouldn’t abandon Frank quite yet. Even though June’s music career suffered greatly while he was associated with Frank, it took June years and Frank umpteen chances before June finally walked away and Frank lost the golden goose forever. Monkey Hill Records is defunct and June has moved on to a bright new day!

*****************

Review of June’s studio album-

Victory Celebration

By Geraldine Wyckoff

MARCH 2, 1998: Waking up on Mardi Gras morning to June Victory’s rhythm-infested, let’s-go-get-em “Down on the Bayou” will definitely put you in the spirit. It’s got that special Mardi Gras Indian, Caribbean-touched beat that is the backbone of so many Mardi Gras songs. It demands that you dance. The tune is the opener of Victory and the Bayou Renegades’ brand-new eponymous CD, which is out just in time for the holiday.

The music here is best described as “the Meters meet the Mardi Gras Indians.” On one hand, you have Victory’s raw guitar and Earl Nunez’s bass producing some mighty deep funk. When they work out on the instrumental “Runaway Indian,” the result is reminiscent of George Porter and Leo Nocentelli grooving with the Meters in the early years. Solid drumming from Jasmin, Victory’s longtime musical partner, keeps that funky edge going.

Then there are the Indian themes and chants like the ones heard on “Hold ‘Em Joe” and “Early in the Morning.” Victory, who spent years performing and recording with Big Chief Bo Dollis and the Wild Magnolias — Victory played on Dollis’ They Call Us Wild and with the chief on the compilation disc Super Sunday Showdown — is firmly rooted in Indian traditions. Those influences are present in his chants and vocal inflections as he sings of Carnival day and the Indian gangs. Victory also is a very melodic musician, one who takes a step off the streets and into the dancehalls. The idiom is broadened by an expanded band that includes the soulful saxophone of Anaray James, the keyboards of Dwight Casanova and the percussion of Norwood “Geechie” Johnson and Patrick Williams.

Tambourines and the whooping and hollering in the background of the fast-paced “Early in the Morning” enhance the energetic feeling of the disc and put the listener in the circle of percussion. Meanwhile, on “Cherie,” Victory and his band move closer to the musical “mainstream” with more standard elements moving from verse to chorus. There’s also a touch of rock ‘n’ roll added to the Indian and funk and accented by Victory’s thoroughly bent guitar notes. The modern blues/rock style of “Take Your Chances” is a passionate love song with a Jimi Hendrix flair. Victory burns this tune up with his seductive guitar work, which is at once minimal and intricate.

Victory quietly creeps into the swamp on “Sometimes You Never Know,” a voodoo-flavored song reminiscent of something you might hear from Dr. John. Victory is alone on the vocals here and demonstrates that even when he’s soft and bluesy, he remains powerful.

There’s a new take on Professor Longhair’s “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” when Victory reworks it as “Mardi Gras Time.” He adds Indian chants like “Big Chief drinking that fire water” to the well-loved Mardi Gras anthem while leaving intact such familiar lyrics as “Got my ticket in my hand, we’re going to go to New Orleans.”

The disc ends with “The Real Deal,” which begins up-tempo and then melts with a Victory guitar slur, only to pick up the rhythm once again. His soloing here and throughout the album is so tasty, and, most important, it lacks the excessiveness that hampers so many other guitarists. Victory leaves room for the rhythm section to jump in, which drives the music and maintains our interest.

The music of June Victory and the Bayou Renegades is totally New Orleans. With its roots in the traditions of Mardi Gras Indians, funk and the swamps, it simply could not originate anywhere else. Particularly during Carnival time, nothing but New Orleans music will do, making this album essential and one that should be in your Carnival music collection. With its many moods and focuses, however, it’s right for any time of year.

June Victory overflows with talent and deserves greater recognition. This album just might be the rhythmic boost to make his a household name among lovers of authentic New Orleans music.

*********************

John Sinclair’s Liner Notes for the June Victory & the Bayou Renegades Live at Tipitina’s CD

The Legendary June Victory is something of an enigmatic presence in the special musical world of New Orleans. An early and powerfully motivated guitar acolyte of the great Jimi Hendrix. June was said to have embraced the rainbow lifestyle of his master as well, living high in some kind of crude commune out in the swamps land and emerging from time to time to engage on stage with his blazing guitar to the amazement of the crowds. In the mid-1970s, June hooked up with Willie Tee’s New Orleans Project and backed up the Wild Magnolias, then moved on to form his own musical Indian band, the Bayou Renegades.

I remember Jerry Brock used to play cuts by the Renegades on WWOZ from a cassette tape of their music that became the band’s first CD release, on Sky Ranch Records in France.

June really hit his artistic stride with the first album he made with Frank Quintini for the Monkey Hill label towards the very end of the 20th century. A driving ensemble, June’s heroic electric guitar and a fine batch of traditional and original Wild Indian songs – including June’s classic, Down on the Bayou– made the self-titled CD a Crescent City favorite.

But there’s nothing quite like seeing and hearing June Victory and the Bayou Renegades on-stage in some steamy New Orleans nightspot, like the night before Mardi Gras at Tipitina’s when Quintini captured the music heard on this splendid set. The band is smoking and completely without restraint, and June’s virtuosic guitar is showcased on everything from Wild Indian songs to out-and-out old school funk rockers to the frantic salute to Jimi Hendrix June offers on All Along the Watchtower.

The album opens with an incredibly wild reworking of Go to the Mardi Gras that’s worth every penny of the price of admission. And, since you’ve no doubt got the CD on the box while you are reading this, let me shut up and get the hell out of the way. Turn it up!

******************

Here’s some information about a very rare June Victory & Bayou Renegades 45 produced on Milton Batiste’s Syla label in the late 1980s. It’s from a really cool blog about FUNK called Home of the Groove. It’s written by Dan Phillips from Lafayette, LA.

RENEGADES JAMMIN’ ON SOME FESS

“Mardi Gras Time (Pt II)” (M.Batiste/W. Victorian/N. Johnson)

Bayou Renegades, Syla, 198?

Listen to: Mardi Gras Time Pt II- Bayou Renegades

Don’t know much about the Bayou Renegades other than that they did some recording for producer Milton Batiste back in the late 1980s-early1990s period and were a jammin’ funk outfit with music influenced by and/or affiliated with Mardi Gras Indians. Only a two cuts they did for Batiste saw the light of day that I am aware of, one of which, “Down On the Bayou” appeared on the various artists compilation CD, New Orleans: A Musical Gumbo, (out of print) that came out on the Mardi Gras label in the 1990s. The other, on this single I found last fall, has the Bayou Renegades on one side and the Olympia Brass Band (which Batiste co-headed with Harold Dejan) doing “Old Lang Syne” on the other. It is unnumbered and likely late 1980s vintage. You may recall that Syla was the label that released Ernie K-Doe’s last 45.

“Mardi Gras Time (Pt II)” is adaptation for Professor Longhair’s “Mardi Gras In New Orleans”, rhythm-heavy with percussion, guitar(s), bass and trumpet (surely Batiste himself) and some Mardi Gras Indian-style whoopin’ and hollerin’ mixed in and around Fess’ lyrics. It’s a loose get-down jam that breaks no new ground but is fine seasonal fun. I don’t have a list of players, but do have some ideas. The songwriters credited are Batiste, W. Victorian, and N. Johnson – the last two of those we’ll get to shortly. But leaving Fess out was certainly a glaring omission and a disservice to the originator; but on a record released only for a brief moment and seen no more, we can let it pass. Anybody in New Orleans who heard it knew the source, anyway.

In 1995, the Bayou Renegades appeared on an obscure CD, The Bayou Renegades Matsue House Party, taken from a live concert recorded in Japan. Half the tunes on it were done by the Renegades and half by Ernie Vincent and his band. The lead guitarist for the BR on the set was June Victory, who had made a name for himself in New Orleans playing in the Wild Magnolias’ stage band. I saw him with them several times, chopping up his rhythm super funky and lighting into his searing solos with abandon. Then in 1998, Victory and the Bayou Renegades released their own eponymous CD on the Monkey hill label. It had the same kind of heavy funk-rock style heard on the Syla single and the live CD; and some of the other players on both CDs were the same: Jasmin on drums, Norwood ‘Geechie’ Johnson on percussion (who also plays with the Wild Magnolias), and Earl Nunez on bass.

Now, going back to the writers’ credits on the single at hand, I’m fairly certain that W. Victorian would be June Victory. “June” is a common nickname for guitarists in New Orleans. And N. Johnson is, of course, ‘Geechie’. So, it appears that the Bayou Renegades were June Victory’s group from the beginning.

*****************

Wilson Victorian was born in 1949 in New Orleans, LA.At the age of 8, he went to Houston to attend the Houston Music School and was taught by Walter Epps. He stayed at the school until age 11, when he returned to New Orleans. June was a musical prodigy.

In the 60s, June recorded his first tune at Tracy Knight’s Studio on Metairie Road. One More Silver Dollar was his first recording. This tune became Midnight Rider by the Allman Brothers Band. By the mid 60s, he formed his first band, the Optimistic Band. He appeared on WGSO-

TV’s live music program with George Benet.

Around this time, June’s Optimistic Band was opening for Chris Kenner, who was riding high on the back of the Sea Saint produced I Like It Like That, Something You Got, and The Land of 1000 Dances.Chris had a real drinking problem, and liked to pre load up on booze before each gig. His driver was Leroy Bates. One time when June was riding with Chris while Leroy was driving, Leroy reached his limit with Chris’ over drinking problem. He screeched the car to a halt, sending Chris forward in the back seat. Leroy grabbed Chris’ bottle of booze, and threw it out the car window. He turned around to Chris and screamed, “I’ve had it with your drinking, and you’re too drunk at your shows!

In the early 70s, he landed at the 809 Club on Bourbon Street at Chris Owens Club with the Mike Christopher Group. He stayed 3 years, gaining major Bourbon Street chops.

June formed the Bayou Band, and backed up Pure Ice, and appeared with McFadden & Whitehead. They had a regional hit, Live & Let Live.He toured throughout Cajun Country, performed with OV Wright and Jackie Wilson, and became the backup band for Sea Saint Studio.

June’s Bayou Band became Sea Saint’s house band, and he backed up a number of artists, including Tony Owens and Leroy Bates.He recorded Down on the Bayou at Back Street Studio, then at Sea Saint Studio.

Also in the 70s, June created his own outdoor concert setting at Phillip and LaSalle Streets, called Cabbage Alley. He built a set of concrete bleachers for seating, which are still there today. He met Monk Boudreaux and Bo Dollis at Cabbage Alley, and both became big fans of the house band, June’s Bayou Band.

June headed to Tennessee where he met William Johnson. He rented a rehearsal spot from ABC Rental in Tennessee. June signed a contact with Johnson, but the Bayou Band had some personnel problems. June regrouped and left town, touring in Arkansas, Georgia, and Tennessee.

June returns to New Orleans and the Bayou Band is kept busy around town with bookings. They favored the Sabou Club near Bayou St. John, and played featured all original tunes. Soon the band was back on the road. When they returned, they worked at the Parisian Club at Jackson and Dryades Streets. The club wasn’t doing well, and the Bayou Band built a large following which saved the club.June felt the club owner wasn’t paying the band properly, a shoot out ensued, and he took his money back. June went to jail for attempted murder and armed robbery.

In the early 80s, June became burnt out and left the music business and opened a construction company. He married and for three years made very good money, and planned his reentry into the music industry.

However, his best laid plans fizzled mightily and June was arrested for drug dealing out West. He met Philip Rose, a gypsy, in jail, and learned the mud jacking business from him. He hooked June up with the hydraulic equipment needed in the mud jacking business. He met Bill Gillem, the inventor of screw piling, and formed a new construction partnership with Bill. Gillem was a great idea developer but lousy businessman and the partnership fizzled. June had an opportunity to sell trucks via his strong contacts in the construction field. This continued for several years.

Via his many relationships in the entertainment business, June started buying poker machines from New York and installing them throughout Jefferson Parish. The government took notice and got involved. Also at this time, the Feds became interested in June’s construction company, and became partners with him. June did an album with Parisian Philippe Le Bras’ Sky Ranch label and Virgin Records while his construction and gambling companies thrived.

Meanwhile, he got involved in the drug trade.

Unfortunately, June’s partner Charlie was a snitch for the Feds, and when June refused to snitch, Charlie’s participation led to June’s arrest. June had sold drugs to Federal undercover agents and he was caught with 5 guns and marked money. He received a 30 year sentence.

Behind the scenes in Court, things were lining up in June’s favor. His attorney called, offering a very unusual deal: Get back in music, and he could walk away from all charges!June called his old friend and fellow musician, Milton Batiste of the Olympia Brass Band, for a record deal, and he the drug and gun charges vanished into thin air.

While all this drama was unfolding, June was busy re-developing his musical style. Norwood Johnson, aka Geegie, a bass player in June’s Bayou Band in the 70s and 80s, remained with the group, and Earl Nunez was brought to play bass drum. The new band configuration was a power trio June named the Power Pack.

Another condition of June’s legal deal was he had to leave Louisiana for a while as a working musician.At 7 am on a Wednesday, June left with the Wild Magnolias, traveling to Minnesota. His band was the “3 Man Crew”. The club was featuring Tracy Chapman, who was in her prime at this time.

June’s new Power Pack band had a funk/Mardi Gras Indian/Psychedelic sound. June had a very good relationship with the club owner so he stayed in Minnesota for a while earning $700/day. He remained in the Wild Magnolias as guitarist. Manager Allison Minor had lined up a record deal in France, so June left Minnesota with Allison for France even though the Minnesota club still wanted June’s services.

Next, Japan beckoned, specifically the Tokyo Roof Club in Tokyo and other clubs in Osaka. Michael Murphy Productions and House of Blues founder Isaac Tigrett sponsored Guitar Battle featuring June, New Orleanian John Mooney, and Japanese funk guitarist June Yamagishi. Mooney performed, and then Yamagishi arrived to back up Mooney. However, Mooney was beaten by Yamagishi. June Victory took up the challenge with Yamagishi, as he wanted to defend Mooney, another American.

Among the Americans involved in this Guitar Battle was Rounder Records, and the PR guy for Michael Jackson. Over breakfast the next morning, the 2 Junes discussed the night before.When June Victory was playing, Yamagishi’s styles conflicted. Yamagishi stopped playing, and Victory began playing solo. He developed a deep rhythm and built a guitar based trance. The deep rhythm wasn’t static, but slipping and sliding. The Japanese audience screamed their approval.

Backstage, Mooney gave Victory a big hug, and the two become fast friends. Yamagishi expresses his desire to move to New Orleans.

June returns to New Orleans, and is put under house arrest.Bass drummer and band member Earl Nunez was assigned to June in Louisiana, as the Court’s conditional house arrest allowed June was outside with a chaperone. June freed Earl and hired good friend and fellow guitar slinger Ernie Vincent, composer of funk classic “Dap Walk” to chaperone. Ernie has always been drug free, which kept away from the drug trade. As with many talented musicians, June has found that drugs or booze hurt his performance, rather than improve it.

As the 90s dawned, June cut the Mardi Gras Indians Super Sunday Showdown with the Wild Magnolias on Rounder Records. The album features Monk Boudreaux & the Golden Eagles, ReBirth Brass Band, Dr. John, Willie Tee, Champion Jack Dupree, John Mooney and Earl Turbinton, Jr., along with Bo Dollis & the Wild Magnolias. The Magnolias’ two tunes on the disc are June’s arrangement- Oops Upside Your Head and Battlefront.

At this time, Rounder Records pursued the Bayou Renegades to sign with them. However the Magnolias had a conflict with Rounder, so the deal stalled. June hired Yamagishi to learn the Magnolias’ material. For a while, the Magnolias featured both Junes on guitar. Yamagishi’s 1994 album Smokin’ Hole (BMG Victor) featured June Victory.

Music and Entertainment attorney Ellis Pailet entered the scene to help the Bayou Renegades obtain convention gigs. June found time to study the law with Ellis as well. Mary Ann McGrath Swaim befriended June, leading to a tour of France with the Sky Ranch label. Mary Duval surfaced with an entertainment company in New Orleans, and took the Magnolias to California.

At this time, June’s relationship with the Wild Magnolias was suffering. Bo Dollis remained June’s ally, but Monk Boudreaux wasn’t. Manager Allison Miner died in 1995 and Glenn Gaines appears. June’s unique Power Pack Trio sound is out and a big band sound with horns and keyboards takes over.

While June’s relationship with the Magnolias suffered, other relationships strengthened. Local anesthesiologist and vinyl junkie Ira “Dr. Ike” Padnos, a huge fan of June’s guitar style and music, hired June to be the house band for the “Flop House” a weekly Sunday house party in an uptown home at the corner of Magazine and Soniat Streets. June utilizes his “3 Man Crew” band version to great acclaim.

As word got out about this weekly event, its popularity grew and grew. Ira supplied the booze and location, June supplied the funk, and there was no stopping until the fete outgrew the neighborhood and had to close. Major parking headaches had developed from all the cars who parked to attend that weeks’ “House Party”.

Meanwhile, things are heating up with the Magnolias. Glenn is proving very difficult to work with. The Magnolias are booked at Tipitinas with the Power Pack Group version of the Magnolias. The Tipitinas gig falls through, and the House of Blues is booked. June has had it with Glenn. The House of Blues show is a big new show for the Magnolias, after a bitter falling out with Glenn, June refuses to rehearse and is fired from the Magnolias. Except for Earl Nunez, Magnolia bass drummer, the entire band walks off. Geechie and Yamagishi perform at the House of Blues gig.

Soon afterwards, Attorney Pailet rebooked the Tipitinas gig for June’s Bayou Band. June’s conditional release from jail required June to be fired instead of him quitting so he met that condition.

June leaves for France, but is sent home by his French and Japanese labels to pick up his foxy, talented female drummer, Jasmin. The World Trade Center wants an escort for June to make sure he leaves the country so he remains out of jail. He goes to Mexico and returns to a record deal with New Orleans boutique label Monkey Hill. The label seemed to have a great future with this roster- Cowboy Mouth, an up and coming New Orleans band featuring the great drummer Fred LeBlanc; Bill Summers &Summer Heat; former DBs front man Peter Holsapple; the Continental Drifters, an all star band featuring Holsapple, Bangles guitarist Vicky Peterson, and Susan Cowsill. The label was started and owned by two men, Jimmy Ford and Frank Quintini.

Within a few years, Ford leaves the label abruptly. When asked what happened, he said to ask Frank. When Mr. Quintini was queried, he provided no answers.What occurred to June Victory answers a lot.

June’s eponymous studio album on Monkey Hill dropped in 1998. The record garnered some amazing reviews and sold pretty well in America and Europe. Has June made any money from the sales? An occasional $20 bill from Frank was all the payments June has received on that album. To get that $20, June would have to go to Frank and ask for it, as a royalty check was never forthcoming. June never received a statement covering sales and never received a signed contract to enforce the deal.

In 2003, Monkey Hill released a live album, June Victory & the Bayou Renegades Live at Tipitinas. This album wasn’t released as widely as the studio album, and again June had no documentation, received zero statements and was paid an infrequent sawbuck or two.

Fall 2005, Hurricane Katrina hits, June eventually evacuates to his long time girlfriend Ivory’s family house in Minnesota. June takes sick with cancer and beats it, thanks to advanced medicine. After treating June poorly for a decade, who shows up in Minnesota to crash for a couple of years? None other than Frank Quintini! Who wrecks June’s new ride, a beautiful Chrysler-Daimler 300 bought in Minnesota? Frank Quintini!

Move forward to 2008, when a few New Orleanians approach the Giacona Container Company, makers of Mardi Gras Throw Cups for many top Mardi Gras Krewes, about producing a new type of Mardi Gras Throw, a Music Medallion. It’s a CD with 5 Mardi Gras tunes in a clear case on a bead. Several major Mardi Gras Krewes purchase this novel throw, including Bacchus, Alla, and Thoth, and all the Mardi Gras supply shops crave it as well. 12,000 units are sold in 3 weeks, meaning the future looks very bright for this new throw. June had 4 tunes on the 4 Music Medallions.

Unfortunately, Frank threatens a Federal suit Giacona over June’s songs, even though his nonexistent contact with June lapsed years ago. Giacona is advised by all partners not to pay, and another artist on the CDs, Ernie Vincent, whom Giacona trusts, talks to Giacona, telling him not to settle.

What does Giacona do? He calls his insurance company, who issues a $3,000 check to Frank’s attorneys. That kills the Music Medallion business. Emboldened by this payoff, Frank tells his attorneys to sue the three New Orleanians who approached Giacona with the Music Medallion concept. So even though there’s no contract, and if there was one it would have lapsed years ago, Frank goes ahead and threatens a Federal copyright suit.

June advises Frank not to sue for the reasons stated in this document, but he disregards his former artist. The case goes nowhere, as by this time, Frank’s attorneys, Booth & Booth, now realize that the suit is garbage and Frank is pursuing another case without any merit. The partners agree to pay a 3 hundred each to make the case disappear and give Frank a few bucks.

When June joined the Monkey Hill label, it was an up and coming New Orleans label with a strong roster. After Jimmy Ford left, the label went on a quick downward spiral, and soon the only act still on board was June Victory. Why? June is a very loyal person, and he wouldn’t abandon Frank quite yet. Even though June’s music career suffered greatly while he was associated with Frank, it took June years and Frank umpteen chances before June finally walked away and Frank lost the golden goose forever. Monkey Hill Records is defunct and June has moved on to a bright new day!

Mardi Gras Indians Seek Copyright Protection For Their Suits

0I’ve met Creole Wild West Chief Howard Miller through my client and good friend, musician June Victory. Chief Howard is a very nice, talented guy who deserves all he can achieve through his art as a Mardi Gras Indian Chief.

Recently he’s filed an online copyright application for his brand new Indian costume in the hopes of collecting some of the income derived from photos, posters, T-Shirts, videos and movies of his costume.

Chief Howard Miller knows cameras will start clicking next month when his Creole Wild West Mardi Gras Indians take to the streets with their elaborately beaded and feathered costumes.

“It’s not about people taking pictures for themselves, but a lot of times people take pictures and sell them,” Miller said.

Intellectual property law dating back to the nation’s founding dictates that apparel and costumes cannot be copyrighted, but Tulane University adjunct law professor Ashlye Keaton has found a way around that by classifying them as something else.

“Their suits and crowns, their regalia, are certainly unique works of art,” Keaton said. “They are entitled to protect that art work.”

Keaton got to know many of the Indians through another Tulane program, the Entertainment Law Legal Assistance Project.

She was intrigued by their art, more so after she saw photos sold at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival and at local galleries, apparently without their permission. Pictures of the Indians sell online for up to $500 each, and books and T-shirts are also available.

Now they and members of the city’s other tribes are working to get a slice of the profits when photos of the towering outfits they have spent the year crafting end up in books and on posters and T-shirts.

Once the costumes are copyrighted, which can be done online for $40, the Indians can either sue people who sell photos of them or try to negotiate licensing fees with photographers either before or after the pictures are taken.

“It’s not about people taking pictures for themselves, but a lot of times people take pictures and sell them,” Miller said.

“For years people have been reaping the benefits from the pictures they take of the Mardi Gras Indians.”

Intellectual property law dating back to the nation’s founding dictates that apparel and costumes cannot be copyrighted, but Tulane University adjunct law professor Ashlye Keaton has found a way around that by classifying them as something else- as works of art.

The first test for the Indians who have copyrighted the new costumes they will wear this year will come at Mardi Gras. The Indians revamp or completely remake their suits every year, and the copyright takes effect at the first public showing, said Ryan Vacca, an assistant professor of law at the University of Akron School of Law.

Once the costumes are copyrighted, which can be done online for $40, the Indians can either sue people who sell photos of them or try to negotiate licensing fees with photographers either before or after the pictures are taken.

“They would be in a good position to negotiate a flat fee or percentage of the sale, something like that,” said Vacca said.

The Mardi Gras Indians have a long and colorful history in New Orleans. Since the end of the 19th century, black men have been making their own version of Indian dress and banding together for informal street parading at Mardi Gras. Local lore holds the tradition sprouted from runaway slaves’ admiration for Native Americans who harbored them from slave hunters before the Civil War.

Mostly the Mardi Gras Indians come from working-class neighborhoods, so their costume investment can take up much of their disposable income.

There is no accurate count of the groups, but about 35 are believed active, many with colorful names such as the Wild Tchoupitoulas, Black Seminoles, Golden Arrows, Wild Magnolias, Fi-Yi-Yi, 7th Ward Hard Head Hunters Golden Blades and Creole Osceola. Each is led by a chief.

Each Indian makes a new suit every year, and over the decades they have become much more glitzy and elaborate. Some cost thousands of dollars.

“It takes the whole year to get ready for Mardi Gras,” Miller said. “I can’t tell you how many hours I put in.”

Miller copyrighted his costume at Keaton’s urging, but it’s unclear how many other Mardi Gras Indians have, since the process has only recently been available online and tracking the old applications is difficult. Miller said he expects many more Indians to copyright their work now that several have done it and can provide help.

He hopes having the copyright will be enough and he will be able to negotiate with photographers and others using his image, rather than sue.

“This is art, what we do,” Miller said. “These suits cost thousands of dollars and all we want is a little bit of what other people make from them.”

“Myth, Mayhem & Majesty: A History of Mardi Gras in New Orleans.”

0

Myth, Mayhem and Majesty: A History of Mardi Gras in New Orleans follows the city’s Carnival traditions, beginning with the celebrations during the French and Spanish colonial periods and in the early days of statehood.

Tuesday–Sunday, February 1–March 4 • Daily at 2:00 p.m. Admission is $5, free for THNOC members. No reservations will be taken for the tour. Discover the origins of New Orleans’s Carnival traditions with Myth, Mayhem & Majesty: A History of Mardi Gras in New Orleans. The popular themed tour of The Collection’s Louisiana History Galleries examines the evolution of Mardi Gras from the colonial period through today and will reveal the insider’s perspective to the fanfare. Featured items from The Collection’s permanent holdings include the earliest written account of Mardi Gras in New Orleans from 1730, a Rex invitation from 1896, and a queen’s scepter from 1920. Please note, The Historic New Orleans Collection will be closed Mardi Gras weekend, Saturday, March 5–Tuesday, March 8.

533 Royal Street • New Orleans, LA 70130

504-523-4662, 504-523-4662 Hours: Tuesday – Saturday 9:30 – 4:30

Royal Street Complex also open on Sunday 10:30 – 4:30

2011 Galveston, TX Mardi Gras

1

I love Texas for many reasons, # 1- my wife of 36 years is from TX.

The info below is from www.galveston.com/mardigras

Don’t miss the revelry at Mardi Gras! Galveston! The island comes alive with 11 extravagant parades, more than 50 galas and festive events, bead throwing, exhibits, live entertainment in local clubs, and the best Gulf Coast cuisine in the world. One of the most popular annual events to take place in Texas, the event is rich with laughter, celebration and people watching. There is something for everyone including a beachfront carnival, shopping, and nightlife featuring everything from Cajun and salsa to jazz and rock and roll.

Rich in history, Mardi Gras! Galveston celebrates its 100th event since it’s inception in 1867. Make your mark in history – attend Mardi Gras! Galveston 2011! Twelve days of fun and entertainment! Beginning on February 25 and it’s not over until the Fat Lady sings! Fat Tuesday, March 8.

“Mardi Gras Galveston is a fun event for the whole family,” said Lou Muller, executive director for the Galveston Island Park Board. “With a variety of activities taking place all across the Island people can be a part of free parades and bead catching or splurge on a luxury gala.”

As part of the family entertainment, there are a number of beachfront and Strand parades ranging from the lavish Knights of Momus Grand Night Parade, Krewe of Gambrinus and Krewe of Aquarius parades; Fire truck Parade, Krewe of Barkus and Meoux (pets and their owners), Children’s Parade (kid size floats with small fry bead throwers), Bicycle Parade and Truck Parade.

Galas include the Annual Treasure Ball Pageant, benefiting Galveston Catholic Schools; Special Peoples Ball, benefiting people with special needs; and Royal Krewe of Barkus & Meoux, benefiting the Galveston Island Humane Society. In addition, there is the renowned San Luis Costume Contest and a whole host of black tie galas at the San Luis Hotel and Resort and the Tremont House.

One of the most popular participants of Galveston Island’s annual celebration, the Philadelphia Mummers, will return in full regalia to the pre-Lenten festivities. Dressed in brilliant ornate costumes, the forty-five member group of strings, banjos and horns, will lead off the Mardi Gras festivities and perform during various events. A spectacle not to be missed, their performance is an Island tradition.

The History of Mardi Gras! Galveston

Galveston’s first recorded Mardi Gras celebration, in 1867, included a masked ball at Turner Hall (Sealy at 21st St.) and a theatrical performance from Shakespeare’s “King Henry IV” featuring Alvan Reed (a justice of the peace weighing in at 350 pounds!) as Falstaff.

The first year that Mardi Gras was celebrated on a grand scale in Galveston was 1871 with the emergence of two rival Mardi Gras societies, or “Krewes” called the Knights of Momus (known only by the initials “K.O.M.”) and the Knights of Myth, both of which devised night parades, masked balls, exquisite costumes and elaborate invitations. The Knights of Momus, led by some prominent Galvestonians, decorated horse-drawn wagons for a torch lit night parade. Boasting such themes as “The Crusades,” “Peter the Great,” and “Ancient France,” the procession through downtown Galveston culminated at Turner Hall with a presentation of tableaux and a grand gala.

Not to be outdone, the Knights of Myth also sponsored a spectacular parade, which, according to a newspaper account, “suddenly sprang out of the bowels of the earth with torch lights, cars and horses.” This parade featured “Pocahontas,” “Scalawag’s Enemies,” and “Bismark’s Grand Band,” and ended at Casino Hall with similar themes and a gala.

In the years that followed, the parades and balls grew more elaborate, glittering with pomp and splendor and attracting attention throughout the state. So grand were plans for the 1872 celebration that newspaper reports declared that this Mardi Gras “promised to eclipse anything ever attempted on Texas soil.” The newly constructed Tremont Opera House, decorated with hundreds of caged canaries “trilling their gladsome voices,” provided a luxurious venue for the staging of tableaux (based on “The Pleasures of the Imagination”) and the evening ball.

By 1873, visitors from around the state were attending the festivities. Among them were Governor E.J. Davis and a party of state officials and legislators who rode in the Mardi Gras parade that year. Dubbed “The Eras of Chivalry,” the parade boasted brilliantly decorated floats fashioned after campaigns and characters from the 6th through the 15th centuries.

By 1880, the street parades proved too extravagant and expensive to continue. However, Mardi Gras masked balls continued to flourish through the end of the century. In 1910, the carnival parades were revived by an organization called the “Kotton Karnival Kids,” a group charged with staging parades for both Mardi Gras and the Galveston Cotton Carnival. This group gave its first dance on February 24, 1914, an historic date marked by Galveston’s first snowfall in 19 years.

The 1917 masked ball took on added glamour with the first official appearance of King Frivolous and his court, who arrived by “royal yacht,” paraded through the streets, and was presented by the mayor with the keys to the city. Characters in that year’s parade were taken from the “comic sheets.”

In 1918, due to the outbreak of World War I, the coronation was canceled and the celebration of Mardi Gras confined to a single day, but the festivities and the coronation of King Frivolous resumed the following year.

Until 1928, the Kotton Karnival Kids-who eventually changed their name to Mystic Merry Makers-continued to sponsor Mardi Gras parades and balls. Themes in those years included “Dante’s Inferno,” “Song and Story,” “The Passing Show,” and “Events of the Year.” The expense of producing the parades and celebrations forced the group to discontinue their sponsorship in 1929, but the Galveston Booster Club saved the day on short notice and continued to sponsor Mardi Gras events until merging with the Galveston Chamber of Commerce in 1937-at which point Mardi Gras came under the Chamber’s authority.

Brilliant and lavish carnivals were celebrated through February 1941, when shortages of men, material and a full commitment to the defeat of the Axis powers by the citizenry of Galveston caused the demise of Mardi Gras on the Island. For nearly 40 years, the annual celebrations were of a private nature, including those hosted by the Maceo family, the Galveston Artillery Club, the Treasure Ball Association and Holy Rosary Catholic Church.

In 1985, native Galvestonian George P. Mitchell and his wife, Cynthia, launched the revival of a citywide Mardi Gras celebration. The Mitchells had long dreamed of restoring the Island’s splendid tradition, and the grand opening of their elegant Tremont House hotel in the historic Strand District provided the spark to do so.

The first year’s spectacular revival featured a mile-long Grand Night Parade saluting “The Age of Mythology.” Nine dazzling floats created by renowned New Orleans float-builder Blaine Kern and hundreds of musicians in marching bands were led by famed jazz clarinetist Pete Fountain through The Strand to the delight of 75,000 cheering spectators. A gala ball, the first Galveston Artwalk and musical performances rounded out a week of festivities.

That same year the 1871 Knights of Momus were revived by several Galvestonians and continues today.

Mardi Gras! Galveston now annually attracts as many as 250,000 revelers throughout the island, which provide a significant boost to the island’s midwinter economy.